Збирач потоків

На війні загинув випускник нашого університету Віталій Блощиця

На війні загинув випускник нашого університету Блощиця Віталій (03.03.1969 – 19.12.2025)... Віталій закінчив Електроакустичний факультет 1994 року (зараз – Факультет електроніки) за спеціальністю «Радіозв'язок, радіомовлення і телебачення» (інженер відео- та звукотехніки).

ST’s AEK-AUD-C1D9031 making audio more accessible with an SPC58 MCU and a FDA903D in the 1st all-in-one AVAS board

The AEK-AUD-C1D9031 is ST’s latest AutoDevKit automotive development platform for audio applications, enabling engineers to play audio with only a microcontroller rather than a far more costly DSP. It features an SPC582B60E1 general-purpose MCU and the FDA903D Class D audio amplifier, which provides current-sensing capabilities. Hence, not only does this combination allow designers to easily and efficiently add audio applications such as simulated engine sounds, but it can also detect if a speaker is disconnected. Moreover, as a standalone MCU system, it offers enhanced resiliency by operating independently from the main infotainment system.

The booming challenges of bringing audio to cars More than just musicThere’s a lot more audio in cars than most assume. When consumers think about it, they typically envision their entertainment system, which remains a critical component. However, there are chimes, warning bells, notification dings, and so many other audio cues that enhance the user experience. In addition, many of them must be available before the entertainment or even the engine is switched on, meaning that not all of them can rely solely on the sound system that drivers and passengers use to listen to music. Furthermore, since electric cars are so quiet, thanks to the absence of a combustion engine, manufacturers add sounds for safety and to improve the user experience.

More than just a central entertainment systemThe problem is that while audio in cars, and acoustic vehicle alerting systems (AVAS) are far from new, they are also not easy to implement and can easily add to the bill of materials. Indeed, the cost of a DSP, an equaliser, and all the components needed by the audio pipeline can quickly add up, which is why many manufacturers opt for a central entertainment system. The problem is that it is a complex system for what are, in effect, computationally trivial tasks, and engineers need to account for safety considerations. For instance, a critical audio warning must still play regardless of the main speaker volume, which requires the design of safeguards and other complex systems.

More than just carsTeams working on modules are also looking to reuse their systems in many more types of vehicles than just the car they originally had in mind. Whether we are talking about two- or three-wheeler trucks or something as small as a forklift, all require AVAS, and being able to reuse a system across many more platforms provides tremendous economies of scale. However, this isn’t possible when using an entertainment system designed primarily to play music from a phone or the radio. Consequently, more and more makers are taking a different approach to audio alerting systems, exploring solutions that are simpler, more cost-effective, and more flexible.

The resounding solutions of the AEK-AUD-C1D9031 The AEK-AUD-C1D9031

A different melody: a new approach to AVAS

The AEK-AUD-C1D9031

A different melody: a new approach to AVAS

The AEK-AUD-C1D9031 is a development platform that helps car makers approach AVAS differently, and many customers have already adopted it to address these challenges. At its core, it is one of the most straightforward systems possible. Playing sound is as simple as sending power to the module. Thanks to its SPC58 microcontroller, it doesn’t need a complex operating system or workarounds to fit a platform designed to perform a myriad of other functions. The AEK-AUD-C1D9031 even demonstrates how developers can use a dedicated mute pin, which makes turning the sound on and off far simpler. Similarly, the current-sensing feature of the FDA903D amplifier means engineers don’t need to add additional components, thus further reducing the bill of materials.

Familiar tunes: common standards and practicesDevelopers can use standard interfaces, which save significant development time. For instance, they can talk to the flash or program the amplifier via an I2C interface, or use I2S to send audio samples. In practice, programmers can play audio samples directly from storage, further eliminating the need for intermediate steps. Developers will have to sample the sounds, as they cannot use a compression format like MP3. For instance, they can play a pre-recorded engine noise from a traditional uncompressed WAVE file and then attach a potentiometer to an AEK-CON-C1D9031 connector board plugged into the AEK-AUD-C1D9031 to interact with the sound.

Indeed, it is possible to run a demo that modifies the sound output based on potentiometers that users can move sideways. By using bit-shifting, developers can lower or increase the pitch. Similarly, increasing or decreasing the number of samples directly impacts playback speed. Hence, it’s through those mechanisms that developers can simulate an engine accelerating or decelerating without using expensive DSPs or EQs. Similarly, the system can generate one note at a time to reproduce complex melodies without having to play a traditional file. In fact, ST developed a demo that uses AutoDevKit and the AEK-AUD-C1D9031 to play the famous Rondo All Turca.

Music to engineers’ ears: more features, less complexity The AEK-CON-C1D9031

The AEK-CON-C1D9031

The AEK-AUD-C1D9031 also shows the advantages of a system independent of the central infotainment system. Since the SPC582B60E1 supports CAN bus, plugging our platform into an existing car safety architecture is simple, enabling engineers to trigger critical alerts very quickly. In most traditional systems, offering all these features would require a far more complex integration process. It’s why we have seen module makers adopt the AEK-AUD-C1D9031. By offering the SPC582B60E1 and the FDA903D on a cost-effective platform, we were able to offer a set of features that help them stand apart, without taking away from the budget they had allocated to other, more costly parts of the vehicle, like the battery management system or onboard charging.

The post ST’s AEK-AUD-C1D9031 making audio more accessible with an SPC58 MCU and a FDA903D in the 1st all-in-one AVAS board appeared first on ELE Times.

Indo-German Tech Cooperation Strengthens with German Ambassador’s visit to R&S India

Rohde & Schwarz India extended a warm welcome to His Excellency Dr. Philipp Ackermann, Ambassador of the Federal Republic of Germany to India, during his visit to the corporate facility located in New Delhi. This significant event signifies a notable advancement in the mutually beneficial relationship between Germany and India. The visit is anticipated to foster increased collaboration in the spheres of advanced technology and innovation, further enhancing the partnership between the two nations.

The Ambassador’s visit aimed to throw light on Rohde & Schwarz’s growing presence over the last three decades, along with highlighting the company’s expanding research and development (R&D) capabilities, planned investments in infrastructure, and enhanced technological competencies, which are also in line with the ‘Make in India’ initiative.

Dr Ackermann was given an overview of the company’s state-of-the-art R&D test laboratories, its work in niche electronics technology areas, and its plans for future innovation and growth during his visit, where he also interacted with the engineering and leadership teams to understand their technical capabilities and long-term vision.

His Excellency Dr Philipp Ackermann remarked:

“It is encouraging to see German technology companies like Rohde & Schwarz making long-term commitments in India. The company’s focus on R&D, local competence development, and high-quality engineering reflects the strong foundation of Indo-German cooperation in technology and innovation.”

Speaking on the occasion, Yatish Mohan, Managing Director, Rohde & Schwarz India, stated: “We are deeply honoured to host His Excellency Dr Ackermann at our facility. This visit underscores our commitment to advancing technological excellence in India and reflects the shared vision of fostering stronger economic and innovation ties between our two nations.”

Rohde & Schwarz India is committed to deepening Indo-German industrial collaboration, driving innovation through local R&D initiatives, and contributing to the nation’s self-reliant manufacturing ecosystem.

The post Indo-German Tech Cooperation Strengthens with German Ambassador’s visit to R&S India appeared first on ELE Times.

Analog semi-automatic lead acid battery tester (sorry for bad english)

| This is my analog semi-automatic battery tester. It mesure battery capacity. Ti does it by discharging the battery via resistor, and measuring current and time. It has analog electronic circuit that automaticly turns the resistor off when battery woltage with load fall to 10,2V. It also turns of the clock, and turns the green LED on. The only thing than you need to do is to look for average current, and look for the time on clock, then you multiple time and current to get capacity. I * t = C 3,2A * 3h = 9,6Ah The circuit is quite complex. On the bottom of the circuit we have BJT with 9,6V zener diode, so it detects when battery voltage is below 10,2V(Base of BTJ isnt getting 0,7V ). When this happens, it lock the BJT and opens the road for voltage to accumulate in capacitor. Once capacitor is charged, it can not be discarged becouse of diode, the only way is vie RESET switch. When capacitor is full, it opens the GATE of MOSFET, and makes the Base of second BJT low, so it stops sending current towards RELAY. RELAY then opens the circuit with resistor and the battery is relieved of load. So its Voltage increses from 10,2V(with load) to 11+V and again makes the base of first BJT high. But it cant discharge capactitor becouse od diode and the circuit remebres the state so it does not osscilate betven load, and no load. When you reset the capacitor, the relay can be turned on. The white LED is simply there becouse i didnt have an oiptimal zener, so i combined one zener with LED to create 9,5V voltage drop. AA batery is for clock. Ive done the test with fully discharged battery, for presentation [link] [comments] |

З Різдвом і Новим роком!

Шановна спільното Київської політехніки! Щиро вітаємо з Різдвом і прийдешнім Новим роком!

Нехай 2026 рік стане часом нових можливостей, професійних і особистих звершень та успіхів, сміливих ідей і вагомих результатів для кожного з нас і для всієї великої родини КПІ.

📋 Для українських науковців продовжено безкоштовний доступ міжнародних наукових ресурсів

У 2026 році для українських університетів та наукових установ продовжено безкоштовний доступ до ключових міжнародних наукових ресурсів, повідомив заступник міністра освіти Денис Курбатов.

Ignoring the regulator’s reference redux

Stephen Woodward’s “Ignoring the regulator’s reference” Design Ideas (DI) (see Figure 1) is an excellent, working example of how to include a circuit in the feedback loop of an op amp to support the stabilization of the circuit’s operating point. This is also previously seen in “Improve the accuracy of programmable LM317 and LM337-based power sources” and numerous other places[1][2][3]). I’ll refer to his DI as “the DI” in subsequent text.

Figure 1 The DI’s Figure 1 schematic has been redrawn to emphasize the positioning of the U1 regulator in the A1 op amp’s feedback loop. The Vdac signal controls U1 while ignoring its internal reference voltage.

Figure 1 The DI’s Figure 1 schematic has been redrawn to emphasize the positioning of the U1 regulator in the A1 op amp’s feedback loop. The Vdac signal controls U1 while ignoring its internal reference voltage.

Wow the engineering world with your unique design: Design Ideas Submission Guide

A few minor tweaks optimize this circuit’s dynamic performance and leave the design equations and comments in the DI unchanged. Let’s consider the case in which U1’s reference voltage is 0.6 V, Vdac varies from 0 to 3 V, and Vo varies from 5 to 0 V.

The DI tells us that in this case, R1a is not populated and that R1b is 150k. It also mentions driving Figure 1’s Vdac from the DACout signal of Figure 2, also found in “A nice, simple, and reasonably accurate PWM-driven 16-bit DAC.”

Figure 2 Each PWM input is an 8-bit DAC. VREF should be at least 3.0 V to support the SN74AC04 output resistances calculable from its datasheet. Ca and C1 – C3 are COG/NPO.

The Figure 2 PWMs could produce a large step change, causing DACout and therefore Vdac to quickly change from 0 to 3 V.

Figure 3 shows how Vo and the output of A1 react to this while driving a hypothetical U1, which is capable of producing an anomaly-free [4] 0-volt output.

Figure 3 Vo and A1’s output from Figure 1 react to a step change in Vdac.

Even though Vo eventually does what it is supposed to, there are several things not to like about these waveforms. Vo exhibits an overshoot and would manifest an undershoot if it didn’t clip at the negative rail (ground). The output of A1 also exhibits clipping and overshooting. Why are these things happening?

The answer is that the current flowing through R5 also flows through R3, causing an immediate change in the output voltage of A1. That change causes a proportional current to flow through R4. However, the presence of C2 prevents an immediate change in Vo and delays compensatory feedback from arriving at A1’s non-inverting input. How can this delay be avoided?

Shorting out R3 makes matters worse. The solution is to remove C2, speeding up the ameliorative feedback. Figure 4 shows the results.

Figure 4 With C2 eliminated, so are the clipping and the over- and undershoots. The A1 output moves only a few millivolts because of the large DC gain of the regulator, and because it is no longer necessary to charge C2 through R4 in response to an input change.

Vo now settles to ½ LSbit of a 16-bit source in 2.5 ms. Changing C3 to 510 pF (10% COG/NPO) reduces that time to 1.4 ms. Smaller values of C3 provide little further advantage.

The Vo-to-VSENSE feedback becomes mostly resistive above 0.159 / (R · C3) Hz, where:

R = R3 + R5 · R1a / (R5 + R1a)

In this case, that’s 1600 Hz, well below the unity gain frequency of pretty much any regulator, and so there should be no stability issues for the overall circuit. Note that A1’s output remains almost exactly equal to the regulator’s reference voltage. This, and the freedom to choose the R5/R1a and R2/R1b ratios, leaves open the option of using an op amp whose inputs and output needn’t approach its positive supply rail.

The (original) DI is a solid design that obtains some dynamic performance benefits from reducing the value of one capacitor and eliminating another.

Related Content

- Ignoring the regulator’s reference

- Improve the accuracy of programmable LM317 and LM337-based power sources

- A nice, simple, and reasonably accurate PWM-driven 16-bit DAC

- Enabling a variable output regulator to produce 0 volts? Caveat, designer!

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Current_mirror#Feedback-assisted_current_mirror

- https://www.onsemi.com/pdf/datasheet/sa571-d.pdf see section on compandor

- https://e2e.ti.com/cfs-file/__key/communityserver-discussions-components-files/14/CircuitCookbook_2D00_OpAmps.pdf see triangle wave generator, page 90

- Enabling a variable output regulator to produce 0 volts? Caveat, designer!

The post Ignoring the regulator’s reference redux appeared first on EDN.

🎥 Новий Навчально-науковий центр «КПІ-Технополіс» у КПІ ім. Ігоря Сікорського

На базі Приладобудівного факультету (ПБФ) відкрито сучасний простір для підготовки інженерів нового покоління. Амбітний проєкт реалізували завдяки Інженерно-технологічному центру «Технополіс», який розробляє та впроваджує комплексні технологічні рішення: від реінжинірингу (проєктування) механічного виробництва або його технологічного аудиту до проєкту обробки під ключ конкретної деталі.

I built an open-source Linux-capable single-board computer with DDR3

| I've made an ARM based single-board computer that runs Android and Linux, and has the same size as the Raspberry Pi 3! Why? I was bored during my 2-week high-school vacation and wanted to improve my skills, while adding a bit to the open-source community :P I ended up with a H3 Quad-Core Cortex-A7 ARM CPU with a Mali400 MP2 GPU, combined with 512MiB of DDR3 RAM (Can be upgraded to 1GiB, but who has money for that in this economy). The board is capable of WiFi, Bluetooth & Ethernet PHY, with a HDMI 4k port, 32 GB of eMMC, and a uSD slot. I've picked the H3 for its low cost yet powerful capabilities, and it's pretty well supported by the Linux kernel. Plus, I couldn't find any open-source designs with this chip, so I decided to contribute a bit and fill the gap. A 4-layer PCB was used for its lower price and to make the project more challenging, but if these boards are to be mass-produced, I'd bump it up to 6 and use a solid ground plane as the bottom layer's reference plane. The DDR3 and CPU fanout was really a challenge in a 4-layer board. The PCB is open-source on the Github repo with all the custom symbols and footprints (https://github.com/cheyao/icepi-sbc). There's also an online PCB viewer here. [link] [comments] |

Active two-way current mirror

EDN Design Ideas (DI) published a design of mine in May of 2025 for a passive two-way current mirror topology that, in analogy to optical two-way mirrors, can reflect or transmit.

That design comprises just two BJTs and one diode. But while its simplicity is nice, its symmetry might not be. That is to say, not precise enough for some applications.

Wow the engineering world with your unique design: Design Ideas Submission Guide

Fortunately, as often happens when the precision of an analog circuit falls short, and the required performance can’t suffer compromise, a fix can consist of adding an RRIO op amp. Then, if we substitute two accurately matched current-sensing resistors and a single MOSFET for the BJTs, the result is the active two-way current mirror (ATWCM) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The active two-way current sink/source mirror. The input current source is mirrored as a sink current when D1 is forward biased, and transmitted as a source current when D1 is reverse biased.

Figure 1 The active two-way current sink/source mirror. The input current source is mirrored as a sink current when D1 is forward biased, and transmitted as a source current when D1 is reverse biased.

Figure 2 shows how the ATWCM operates when D1 is forward-biased, placing it in mirror mode.

Figure 2 ATWCM in mirror mode, I1 sink current generates Vr, forcing A1 to coax Q1 to mirror I2 = I1.

The operation of the ATWCM in mirror mode couldn’t be more straightforward. Vr = I1R wired to A1’s noninverting input forces it to drive Q1 to conduct I2 such that I2R = I1R.

Therefore, if the resistors are equal, A1’s accuracy-limiting parameters (offset voltage, gain-bandwidth, bias and offset currents, etc.) are adequately small, and Q1 does not saturate, I1 = I2 just as precisely as you like.

Okay, so I lied. Actually, the operation of the ATWCM in transmission mode is even simpler, as Figure 3 shows.

Figure 3 ATWCM in transmission mode. A reverse-biased D1 means I1 has nowhere to go except through the resistors and (saturated and inverted) Q1, where it is transmitted back out as I2.

I1 flowing through the 2R net resistance forces A1 to rail positive, saturating Q1 and providing a path back to the I2 pin. Since Q1 is biased inverted, its body diode will close the circuit from I1 to I2 until A1 takes over. A1 has nothing to do but act as a comparator.

Flip D1 and substitute a PFET for Q1, and of course, a source/sink will result, shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Source/sink two-way mirror with a D1 flipped the opposite direction, and Q1 replaced with a PFET.

Figure 5 shows the circuit in Figure 4 running a symmetrical rail-to-rail tri-wave and square-wave output multivibrator.

Figure 5 Accurately symmetrical tri-wave and square-wave result from inherent A1Q2 two-way mirror symmetry.

Stephen Woodward’s relationship with EDN’s DI column goes back quite a long way. Over 100 submissions have been accepted since his first contribution back in 1974.

Related Content

- A two-way mirror—current mirror that is

- Active current mirror

- A current mirror reduces Early effect

- A two-way Wilson current mirror

The post Active two-way current mirror appeared first on EDN.

Aiding drone navigation with crystal sensing

Designers are looking to reduce the cost of drone systems for a wide range of applications but still need to provide accurate positioning data. This however is not as easy is it might appear.

There are several satellite positioning systems, from the U.S.-backed GPS and European Galileo to NavIC in India and Beidou in China, providing data down to the meter. However, these need to be augmented by an inertial measurement unit (IMU) that provides more accurate positioning data that is vital.

Figure 1 An IMU is vital for the precision control of the drone and peripherals like gimbal that keeps the camera steady. Source: Epson

An IMU is typically a sensor that can measure movement in six directions, along with an accelerometer to detect the amount of movement. The data is then used by the developer of an inertial measurement system (IMS) with custom algorithms, often with machine learning, combined with the satellite data and other data from the drone system.

The IMU is vital for the precision control of the drone and peripherals such as the gimbal that keeps the camera steady, providing accurate positioning data and compensating for the vibration of the drone. This stability can be implemented in a number of ways with a variety of sensors, but providing accurate information with low noise and high stability for as long as possible has often meant the sensor is expensive with high power consumption.

This is increasingly important for medium altitude long endurance (MALE) drones. These aircraft are designed for long flights at altitudes of between 10,000 and 30,000 feet, and can stay airborne for extended periods, sometimes over 24 hours. They are commonly used for military surveillance, intelligence gathering, and reconnaissance missions through wide coverage.

These MALE drones need a stable camera system that is reliable and stable in operation and a wide range of temperatures, providing accurate tagging of the position of any data captured.

One way to deliver a highly accurate IMU with lower cost is to use a piezoelectric quartz crystal. This is well established technology where an oscillating field is applied across the crystal and changes in motion are picked up with differential contacts across the crystal.

For a highly stable IMU for a MALE drone, three crystals are used, one for each axis, stimulated at different frequencies in the kilohertz range to avoid crosstalk. The differential output cancels out noise in the crystal and the effect of vibrations.

Precision engineering of piezoelectric crystals for high-stability IMUs

Using a crystal method provides data with low noise, high stability, and low variability. The highly linear response of the piezoelectric crystal enables high-precision measurement of various kinds of movement over a wide range from slow to fast, allowing the IMU to be used in a broad array of applications.

An end-to-end development process allows the design of each crystal to be optimized for the frequencies used for the navigation application along with the differential contacts. These are all optimized with the packaging and assembly to provide the highly linear performance that remains stable over the lifetime of the sensor.

It uses 25 years of experience with wet etch lithography for the sensors across dozens of patents. That produces yields in the high nineties with average bias variations, down to 0.5% variant from unit to unit.

An initial cut angle on the quartz crystal achieves the frequency balance for the wafer, then the wet etch lithography is applied to the wafer to create a four-point suspended cantilever structure that is 2-mm long. Indentations are etched into the structure for the wire bonds to the outside world.

The four-point structure is a double tuning fork with detection tines and two larger drive tines in the centre. The differential output cancels out spurious noise or other signals.

This is simpler to make than micromachined MEMS structures and provides more long-term stability and less variability across the devices.

The differential structure and low crosstalk allow three devices to be mounted closely together without interfering with each other, which helps to reduce the size of the IMU. A low pass filter helps to reduce any risk of crosstalk.

The six-axis crystal sensor is then combined with an accelerometer for the IMU. For the MALE drone gimbal applications, this accelerometer must have a high dynamic range to handle the speed and vibration effects of operation in the air. The linearity advantage of using a piezoelectric crystal provides accuracy for sensing the rotation of the sensor and does not degrade with higher speeds.

Figure 2 Piezoelectric crystals bolster precision and stability in IMUs. Source: Epson

This commercial accelerometer is optimized to provide the higher dynamic range and sits alongside a low power microcontroller and temperature sensors, which are not common in low-cost IMUs currently used by drone makers.

The microcontroller technology has been developed for industrial sensors over many years and reduces the power consumption of peripherals while maintaining high performance.

The microcontroller is used to provide several types of compensation, including temperature and aging, and so provides a simple, stable, and high-quality output for the IMU maker. Quartz also provides very predictable operation across a wide temperature range from -40 ⁰C to +85 ⁰C, so the compensation on the microcontroller is sufficient and more compensation is not required in the IMU, reducing the compute requirements.

All of this is also vital for the calibration procedure. Ensuring that the IMU can be easily calibrated is key to keeping the cost down and comes from the inherent stability of the crystal.

Calibration-safe mounting

The mounting technology is also key for the calibration and stability of the sensor. A part that uses surface mount technology (SMT), such as a reflow oven, for mounting to a board, which is exposed to high temperatures that can disrupt the calibration and alter the lifetime of the part in unexpected ways.

Instead, a module with a connector is used, so the 1-in (25 x 25 x 12 mm) part can be soldered to the printed circuit board (PCB). This avoids the need to use the reflow assembly for surface mount devices where the PCB passes through an oven, which can upset the calibration of the sensor.

Space-grade IMU design

A higher performance variant of the IMU has been developed for space applications. Alongside the quartz crystal sensor, a higher performance accelerometer developed in-house is used in the IMU. The quartz sensor is inherently impervious to radiation in low and medium earth orbits and is coupled with a microcontroller that handles the temperature compensation, a key factor for operating in orbits that vary between the cold of the night and the heat of the sun.

The sensor is mounted in a hermetically sealed ceramic package that is backfilled with helium to provide higher levels of sensitivity and reliability than the earth-bound version. This makes the quartz-based sensor suitable for a wide range of space applications.

Next-generation IMU development

The next generation of etch technology being explored now promises to enable a noise level 10 times lower than today with improved temperature stability. These process improvements enable cleaner edges on the cantilever structure to enhance the overall stability of the sensor.

Achieving precise and reliable drone positioning requires the integration of advanced IMUs with satellite data. The use of piezoelectric quartz crystals in IMUs for drone systems offers significant benefits, including low noise, high stability, and reduced costs, while commercial accelerometers and optimized microcontrollers further enhance performance and minimize power consumption.

Mounting and calibration procedures ensure long-term accuracy and reliability to provide stable and power-efficient control for a broad range of systems. All of this is possible through the end-to-end expertise in developing quartz crystals, and designing and implementing the sensor devices, from the etch technology to the mounting capabilities.

David Gaber is group product manager at Epson.

Related Content

- Exploring ceramic resonators and filters

- Drone design: An electronics designer’s point of view

- How to design an ESC module for drone motor control

- Keep your drone flying high with the right circuit protection design

- ST Launches AI-Enabled IMU for Activity Tracking and High-Impact Sensing

The post Aiding drone navigation with crystal sensing appeared first on EDN.

Баскетбол. Студентська ліга м. Києва. Стартуємо гучно!

💥Офіційно стартувала Молодіжна студентська ліга м. Києва. Збірна КПІ під керівництвом Олега Яременко та Григорія Устименко розпочала сезон у Дивізіоні А — і зробила це максимально впевнено 💪

MicroLink Devices UK awarded in Call 2 of CSconnected Supply Chain Development Programme

Tuneful track-tracing

Another day, another dodgy device. This time, it was the continuity beeper on my second-best DMM. Being bored with just open/short indications, I pondered making something a little more informative.

Perhaps it could have an input stage to amplify the voltage, if any, across current-driven probes, followed by a voltage-controlled tone generator to indicate its magnitude, and thus the probed resistance. Easy! . . . or maybe not, if we want to do it right.

Wow the engineering world with your unique design: Design Ideas Submission Guide

Figure 1 shows the (more or less) final result, which uses a carefully-tweaked amplifying stage feeding a pitch-linear VCO (PLVCO). It also senses when contact has been made, and so draws no power when inactive.

Most importantly, it produces a tone whose musical pitch is linearly related to the sensed resistance: you can hear the difference between fat power traces and long, thin signal ones while probing for continuity or shorts on a PCB without needing to look at a meter.

Figure 1 A power switch, an amplifying stage with some careful offsets, and a pitch-linear VCO driving an output transducer make a good continuity tester. The musical pitch of the tone produced is proportional to the resistance across the probe tips.

Figure 1 A power switch, an amplifying stage with some careful offsets, and a pitch-linear VCO driving an output transducer make a good continuity tester. The musical pitch of the tone produced is proportional to the resistance across the probe tips.

This is simpler than it initially looks, so let’s dismantle it. R1 feeds the test probes. If they are open-circuited, p-MOSFET Q1 will be held off, cutting the circuit’s power (ignoring <10 nA leakage).

Any current flowing through the probes will bring Q1.G low to turn it on, powering the main circuit. That also turns Q2 on to couple the probe voltage to A1a.IN+ via R2. Without Q2, A1a’s input protection diodes would draw current when power was switched off.

R1 is shown as 43k for an indication span of 0 to ~24 Ω, or 24 semitones. Other values will change the range, so, for example, 4k3 will indicate up to 2.4 Ω with 0.1-Ω semitones. Adding a switch gave both ranges. (The actual span is up to ~30 Ω—or 3.0 Ω—but accuracy suffers.) Any other values can be used for different scales; the probe current will, of course, change.

A1a amplifies the probe voltage by 1001-ish, determined by R3 and R4. We are working right down to 0 V, which can be tricky. R5 offsets A2a.IN- by ~5 mV, which is more than the MCP6002’s quoted maximum input offset of 3.5 mV. R2 and R6–8 help to add a slightly greater bias to A1a.IN+ that both null out any offset and set the operating point. This scheme may avert the need for a negative rail in other applications.

Tuning the tones

The A1b section is yet another variant on my basic pitch-linear VCO, the reset pulse being generated by Q4/C3/R13. (For more informative details of the circuit’s general operation, see the original Design Idea.) The ’scope traces in Figure 2 should clarify matters.

Figure 2. Waveforms within the circuit to show its operation while probing different resistances.

This type of PLVCO works best with a control voltage centered between the supply rails and swinging by ±20% about that datum, giving a bipolar range of ~±1 octave. Here, we need unipolar operation, starting around that -20% lowest-frequency point.

Therefore, 0 Ω on the input must give ~0.3 Vcc to generate a ~250 Hz tone; 12 Ω, 0.5 Vcc (for ~500 Hz); and 24 Ω, ~0.7 Vcc (~1 kHz). Anything above ~0.8 Vcc will be out of range—and progressively less accurate—and must be ignored.

The output is now a tone whose pitch corresponds to the resistance across the probes, scaled as one semitone per ohm and spanning two octaves for a 24 Ω range (if R1 is 43k).

The modified exponential ramp on C2 is now sliced by A2b, using a suitable fraction of the control voltage as a reference, to give a “square” wave at its output—truly square at one point only, but it sounds OK, and this approach keeps the circuit simple. A2a inverts A2b’s output, so they form a simple balanced (or bridge-tied load) driver for an earpiece. (There are problems here, but they can wait.)

R9 and R10 reduce A1a’s output a little as high resistances at the input cause it to saturate, which would otherwise stop A1b’s oscillation. This scheme means that out-of-range resistances still produce an audio output, which is maxed out at ~1.6 kHz, or ~30 Ω. Depending on Q1’s threshold voltage, several tens of kΩs across the probes are enough to switch it on—a tad outside our indication range.

Loud is allowed

Now for that earpiece, and those potential problems. Figure 1’s circuit worked well enough with an old but sensitive ~250-Ω balanced-armature mic/’phone but was fairly hopeless when trying to drive (mostly ~32 Ω) earphones or speakers.

For decent volume, try Figure 4, which is beyond crude, but functional. Note the separate battery, whose use avoids excessive drain on the main one while isolating the main circuit from the speaker’s highish currents.

Again, no power is drawn when the unit is inactive. (Reused batteries—strictly, cells—from disposed-of vapes are often still half-full, and great for this sort of thing! And free.) A2a is now spare . . .

Figure 3 A simple, if rather nasty, way of driving a loudspeaker.

Setting-up is necessary, because offsets are unpredictable, but simple. With a 12-Ω resistance across the probes, adjust R7 to give Vcc/2 at A1b.5. Done!

Comments on the components

The MCP6002 dual op-amp is cheap and adequate. (The ’6022 has a much lower offset but a far higher price, as well as drawing more current. “Zero-offset” devices are yet more expensive, and trimmer R7 would probably still be needed.)

Q3, and especially Q1, must have a low RDS(on) and VGS(th); my usual standby ZVP3306As failed on both counts, though ZVN3306As worked well for Q2/4/5. (You probably have your own favorite MOSFETs and low-voltage RRIO op-amps.) To alter the frequency range, change C2. Nothing else is critical.

As noted above, R1 sets the unit’s sensitivity and can be scaled to suit without affecting anything else. With 43k, the probe current is ~70 µA, which should avoid any possible damage to components on a board-under-test.

(Some ICs’ protection diodes are rated at a hopefully-conservative 100 µA, though most should handle at least 10 mA.) R2 helps guard against external voltage insults, as well as being part of the biasing network.

And that newly-spare half of A2? We can use it to make an active clamp (thanks, Bob Dobkin) to limit the swing from A1a rather than just attenuating it. R1 must be increased—51k instead of 43k—because we no longer need extra gain.

Figure 4 shows the circuit. When A2a’s inverting input tries to rise higher than its non-inverting one—the reference point—D1 clamps it to that reference voltage.

Figure 4. An active clamp is a better way of limiting the maximum control voltage fed to the PLVCO.

The slight frequency changes with supply voltage can be ignored; a 20°C temperature rise gave an upward shift of about a semitone. Shame: with some careful tuning, this could otherwise also have done duty as a tuning fork.

“Pitch-perfect” would be an overstatement, but just like the original PLVCO, this can be used to play tunes! A length of suitable resistance wire stretched between a couple of drawing pins should be a good start . . . now, where’s that half-dead wire-wound pot? Trying to pick out a seasonal “Jingle Bells” could keep me amused for hours (and leave the neighbors enraged for weeks).

—Nick Cornford built his first crystal set at 10, and since then has designed professional audio equipment, many datacomm products, and technical security kit. He has at last retired. Mostly. Sort of.

Related Content

- Power amplifiers that oscillate— Part 2: A crafty conclusion.

- Revealing the infrasonic underworld cheaply, Part 2

- A pitch-linear VCO, part 2: taking it further

- 5-V ovens (some assembly required)—part 2

The post Tuneful track-tracing appeared first on EDN.

You asked for it

| Hello everyone, last week I posted my AM radio in a 4layer pcb design. I got loads of good suggestions as well as people saying that 4layers was overkill. Here is the two layer design! And thanks for all the suggestions I may upgrade this design using transistors to amplify the rf signal. [link] [comments] |

Інженерні тижні «KPISchool» для учнів 9–11 класів у КПІ ім. Ігоря Сікорського

З 29 грудня 2025 року по 10 січня 2026 року в Національному технічному університеті України «Київський політехнічний інститут імені Ігоря Сікорського» відбудуться Інженерні тижні «KPISchool» — освітній профорієнтаційний захід у межах проєкту «Майбутній КПІшник».

Fuji Electric and Robert Bosch collaborate on SiC power semiconductor modules for EVs

Spunking Cock Christmas Lights

http://pigeonsnest.co.uk/stuff/cocklights.html

"It has to be said that the main reason I have bothered to publish this circuit at all is that it means I can post a diagram of a circuit with a !SPUNK_ENABLE line in it."

Happy Christmas! :-)

(I recently came across this website and there's a lot of interesting stuff there, if you can past the F-bombs. The article on magnetic core saturation is superb!)

[link] [comments]

Exploring ceramic resonators and filters

Ceramic resonators and filters occupy a practical middle ground in frequency control and signal conditioning, offering designers cost-effective alternatives to quartz crystals and LC networks. Built on piezoelectric ceramics, these devices provide stable oscillation and selective filtering across a wide range of applications—from timing circuits in consumer electronics to noise suppression in RF designs.

Their appeal lies in balancing performance with simplicity: easy integration, modest accuracy, and reliable operation where ultimate precision is not required.

Getting started with ceramic resonators

Ceramic resonators offer an attractive alternative to quartz crystals for stabilizing oscillation frequencies in many applications. Compared with quartz devices, their ease of mass production, low cost, mechanical ruggedness, and compact size often outweigh the reduced precision in frequency control.

In addition, ceramic resonators are better suited to handle fluctuations in external circuitry or supply voltage. By relying on mechanical resonance, they deliver stable oscillation without adjustment. These characteristics also enable faster rise times and performance that remains independent of drive-level considerations.

Recall that ceramic resonators utilize the mechanical resonance of piezoelectric ceramics. Quartz crystals remain the most familiar resonating devices, while RC and LC circuits are widely used to produce electrical resonance in oscillating circuits. Unlike RC or LC networks, ceramic resonators rely on mechanical resonance, making them largely unaffected by external circuitry or supply-voltage fluctuations.

As a result, highly stable oscillation circuits can be achieved without adjustment. Figure below shows two types of commonly available ceramic resonators.

Figure 1 A mix of common 2-pin and 3-pin ceramic resonators demonstrates their typical package styles. Source: Author

Ceramic resonators are available in both 2-pin and 3-pin versions. The 2-pin type requires external load capacitors for proper oscillation, whereas the 3-pin type incorporates these capacitors internally, simplifying circuit design and reducing component count. Both versions provide stable frequency control, with the choice guided by board space, cost, and design convenience.

Figure 2 Here are the standard circuit symbols for 2-pin and 3-pin ceramic resonators. Source: Author

Getting into basic oscillating circuits, these can generally be grouped into three categories: positive feedback, negative resistance elements, and delay of transfer time or phase. For ceramic resonators, quartz crystal resonators and LC oscillators, positive feedback is the preferred circuit approach.

And the most common oscillator circuit for a ceramic resonator is the Colpitts configuration. Circuit design details vary with the application and the IC employed. Increasingly, oscillation circuits are implemented with digital ICs, often using an inverter gate. A typical practical example (455 kHz) with a CMOS inverter is shown below.

Figure 3 A practical oscillator circuit employing a CMOS inverter and ceramic resonator shows its typical configuration. Source: Author

In the above schematic, IC1A functions as an inverting amplifier for the oscillating circuit, while IC1B shapes the waveform and buffers the output. The feedback resistor R1 provides negative feedback around the inverter, ensuring oscillation starts when power is applied.

If R1 is too large and the input inverter’s insulation resistance is low, oscillation may stop due to loss of loop gain. Excessive R1 can also introduce noise from other circuits, while being too small a value reduces loop gain.

The load capacitors C1 and C2 provide a 180° phase lag. Their values must be chosen carefully based on application, integrated circuit, and frequency. Undervalued capacitors increase loop gain at high frequencies, raising the risk of spurious oscillation. Since oscillation frequency is influenced by loading capacitance, caution is required when tight frequency tolerance is needed.

Note that the damping resistor R2, sometimes omitted, loosens the coupling between the inverter and feedback circuit, reducing the load on the inverter output. It also stabilizes the feedback phase and limits high-frequency gain, helping prevent spurious oscillation.

Having introduced the basics of ceramic resonators (just another surface scratch), we now shift focus to ceramic filters. The deeper fundamentals of resonator operation can be addressed later or explored through further discussion; for now, the emphasis turns to filter applications.

Ceramic filters and their practical applications

A filter is an electrical component designed to pass or block specific frequencies. Filters are classified by their structures and the materials used. A ceramic filter employs piezoelectric ceramics as both an electromechanical transducer and a mechanical resonator, combining electrical and mechanical systems within a single device to achieve its characteristic response.

Like other filters, ceramic filters possess unique traits that distinguish them from alternatives and make them valuable for targeted applications. They are typically realized in bandpass configurations or as duplexers, but not as broadband low-pass or high-pass filters, since ceramic resonators are inherently narrowband.

In practice, ceramic filters are widely used in IF and RF bandpass applications for radio receivers and transmitters. These RF and IF ceramic filters are low-cost, easy to implement, and well-suited for many designs where the precision and performance of a crystal filter are unnecessary.

Figure 4 A mix of ceramic filters presents examples of their available packages. Source: Author

A quick theory talk: A 455-kHz ceramic filter is essentially a bandpass filter with a sharp frequency response centered at 455 kHz. In theory, attenuation at the center frequency is 0 dB, though in practice insertion loss is typically 2–6 dB. As the input frequency shifts away from 455 kHz, attenuation rises steeply.

Depending on the filter grade, the effective passband spans from about 455 kHz ± 2 kHz for narrow designs and up to ±15 kHz for wider types (in theory often cited as ±10 kHz). Signals outside this range are strongly suppressed, with stopband attenuation reaching 40 dB or more at ±100 kHz.

On a related note, ceramic discriminators function by converting frequency variations into voltage signals, which are then processed into audio detection method widely used in FM receivers. FM wave detection is achieved through circuits where the relationship between frequency and output voltage is linear. Common FM detection methods include ratio detection, Foster-Seeley detection, quadrature detection, and differential peak detection.

Now I recall the CDB450C24, a ceramic discriminator designed for FM detection at 450 kHz. Employing piezoelectric ceramics, it provides a stable center frequency and linear frequency-to-voltage conversion, making it well-suited for quadrature detection circuits such as those built with the nostalgic Toshiba TA31136F FM IF detector IC for cordless phones. Compact and cost‑effective, the CDB450C24 exemplifies the role of ceramic discriminators in reliable FM audio detection.

Figure 5 TA31136F IC application circuit shows the practical role of the CDB450C24. Source: Toshiba

As a loosely connected observation, the choice of 450 kHz for ceramic discriminators reflected receiver design practices of the time. AM radios had long standardized on 455 kHz as their intermediate frequency (IF), while FM receivers typically used 10.7 MHz for selectivity.

To achieve cost-effective FM detection, however, many designs employed a secondary IF stage around 450 kHz, where ceramic discriminators could provide stable, narrowband frequency-to-voltage conversion.

This dual-IF approach balanced the high-frequency selectivity of 10.7 MHz with the practical detection capabilities of 450 kHz, making ceramic discriminators like the CDB450C24 a natural fit for FM audio demodulation.

Thus, ceramic filters remain vital for compact, reliable frequency selection, valued for their stability and low cost. Multipole ceramic filters extend this role by combining multiple resonators to sharpen selectivity and steepen attenuation slopes, their real purpose being to separate closely spaced channels and suppress adjacent interference.

Together, they illustrate how ceramic technology continues to balance simplicity with performance across consumer and professional communication systems.

Closing thoughts

Time for a quick pause—but before you step away, consider how ceramic resonators and filters continue to anchor reliable frequency control and signal shaping across modern designs. Their balance of simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and performance makes them a quiet force behind countless applications.

Share your own experiences with these components and keep an eye out for more exploration into the fundamentals that drive today’s electronics.

T. K. Hareendran is a self-taught electronics enthusiast with a strong passion for innovative circuit design and hands-on technology. He develops both experimental and practical electronic projects, documenting and sharing his work to support fellow tinkerers and learners. Beyond the workbench, he dedicates time to technical writing and hardware evaluations to contribute meaningfully to the maker community.

T. K. Hareendran is a self-taught electronics enthusiast with a strong passion for innovative circuit design and hands-on technology. He develops both experimental and practical electronic projects, documenting and sharing his work to support fellow tinkerers and learners. Beyond the workbench, he dedicates time to technical writing and hardware evaluations to contribute meaningfully to the maker community.

Related Content

- SAW-filter lead times stretching

- Murata banks on ceramic technology

- Ceramic packages stage a comeback

- Multilayer ceramics ups performance

- SAW filters and resonators provide cheap and effective frequency control

The post Exploring ceramic resonators and filters appeared first on EDN.

From Hype to Reality: The Three Forces defining Security in 2026

By Andrew Burnett, Interim Chief Technology Officer, Milestone Systems

As we move into 2026, several technology trends that were once mostly confined to research labs and conference keynotes are now stepping into the daily reality of the security industry. What is new today is not the idea of AI itself, but the emergence of Agentic AI – intelligent systems capable of taking autonomous actions across operational workflows. Rather than asking what they might one day do, we are now seeing what they actually do in the field.

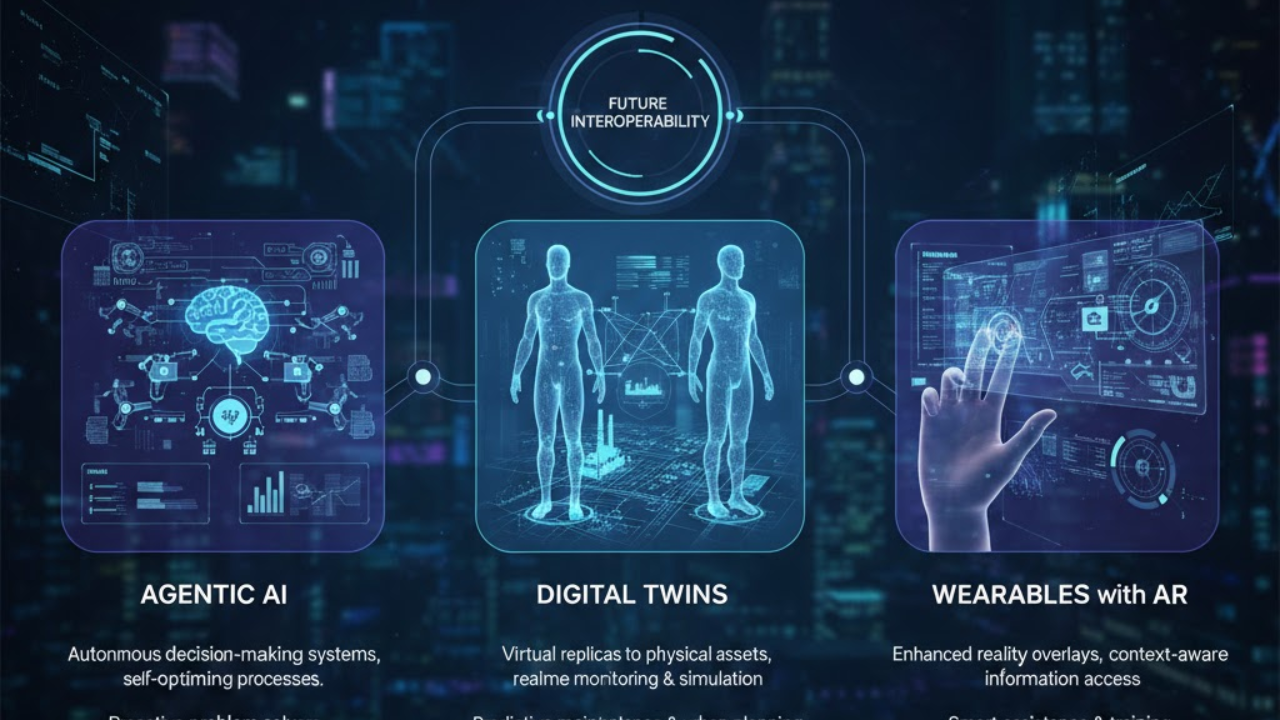

In 2026, three technologies will particularly drive this transformation: Agentic AI, Digital Twins and Wearables with Augmented Reality (AR). Each represents an evolution not just in capability, but a step toward fully intelligent, interconnected and immersive security ecosystems.

As India accelerates its adoption of smart city frameworks and digital surveillance infrastructure through national programs like the Smart Cities Mission (https://smartcities.data.gov.in/)and the Digital India initiative (https://www.digitalindia.gov.in/), technologies such as Agentic AI, Digital Twins, and AR-enabled wearables are no longer futuristic concepts—they are becoming essential to the daily functioning of security operations across Indian enterprises, public infrastructure, and government systems.

- Agentic AI — From Hype-Cycle to Operational Workflows

Agentic AI, first notable for its capabilities in areas like code generation, is now expanding beyond coding to orchestrate operational workflows across security systems. The shift for 2026 is from capability demonstrations to task-focused agents embedded in operational flows. Rather than one-off proof of concept, we are seeing agents that orchestrate across systems: they ingest video, correlate access logs, detect deviations and then trigger follow-up actions – all without a human translating between disparate interfaces.

According to Indian reports:

- The AI for Viksit Bharat study states that Financial services companies’ front, middle and back offices are expected to be transformed by machine learning and agentic AI.

- The Ministry of Electronics & IT, India’s AI Revolution, notes that AI-driven technologies, such as autonomous agents, are helping SMBs scale efficiently, personalise customer experiences, and optimise operations.

Practical examples include autonomous investigation agents that not only take an alarm, gather the last 30 minutes of multimodal evidence (video, access, sensor telemetry), but also propose and initiate immediate mitigation action for an operator to approve. The value is twofold: speed (reducing mean time to insight) and bandwidth (freeing operators to focus on decisions, not data-gathering).

This momentum is mirrored in global investment patterns. According to recent industry projections, Agentic AI is set to dominate IT budget expansion over the next five years, representing more than 26% of worldwide IT spending and surpassing US$1.3 trillion by 2029. This reflects a decisive shift: organisations are no longer experimenting with AI for select projects – they are operationalising it at scale.

Organisations should stop asking “what might agentic AI do” and start identifying the repeatable security workflows they want automated; for example, incident triage, patrol optimisation, evidence packaging; then measure agent performance against those KPIs. The winners in 2026 will be platforms that expose safe, auditable agent APIs and vendors who integrate them into end-to-end operational playbooks.

- Digital Twins – Moving from Models to Mission-Critical Decisions

Digital twins — the highly sophisticated virtual models that stay synchronised with real-world systems — are also reaching a point of true practicality. The concept is not new. For years, industries like manufacturing and logistics have used digital twins to monitor assets and environments. What’s new is the granularity and scale now possible in security.

According to the Ministry of Communications in India, AI-driven Digital Twins integrate real-time, cross-sectoral data from various sources in a privacy-preserving manner, ensuring a unified and dynamic planning process ensuring integrated planning and fostering a collaborative ecosystem. Digital Twins enable continuous real-time monitoring and predictive analytics. AI enhances data-driven decision-making by simulating multiple scenarios, optimising resource allocation, and improving infrastructure resilience under various conditions.

Organisations such as NVIDIA are utilising digital twins for data centres, integrating cameras, fire alarms, access control and environmental sensors to create a unified, real-time view of operations. Instead of static replicas, we are talking about interactive environments where you can safely test and optimise system behaviour. The value of digital twins goes beyond visualisation and simulation, empowering organisations to monitor, optimise, and actively manage the desired state of multiple subsystems in real-time.

Imagine running a virtual fire-drill scenario that shows pedestrian flow if a corridor is blocked, or simulating lockout strategies to maintain egress while containing a threat. These are not academic exercises — they directly inform SOPs, layout choices and where to place resilient communications or edge compute. For complex estates (airports, ports, multi-tenant high-rises), a unified digital twin reduces configuration drift, accelerates forensic reconstruction and enables predictive maintenance for critical devices.

Looking ahead, the widespread adoption of digital twins is poised to reshape the security industry’s approach to risk management and operational planning. With a unified, real-time view of complex environments, digital twins enable proactive decision-making, allowing security teams to anticipate threats, optimise resource allocation and continuously refine standard operating procedures. Over time, this capability will shift the industry from reactive incident response to predictive and preventative security strategies, where investment in training, infrastructure and technology is guided through simulated outcomes rather than historical events.

- From Gadgets to Game-Changers: Wearables + AR in Action

AR and wearables have had a turbulent history, but their resurgence in 2026 will be different — and AI is the reason. AI transforms wearables from simple capture devices into intelligent companions. It elevates AR from a visual overlay to a real-time, context-aware guidance layer. They shift frontline tools from passive to proactive devices that see, listen, and interpret the environment, delivering timely insights and support through voice, visual or hybrid interfaces.

Government of India, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology states: India is now prepping for cutting-edge technologies, including 5G, AI, blockchain, augmented reality & virtual reality, machine learning & deep learning, robots, natural language processing, etc.

The momentum behind AR is also reflected in the market. Globally, the AR sector is projected to surge from US$35.8 billion in 2024 to US$233.3 billion by 2030, a compound annual growth rate of 37%. Today, software and services account for the vast majority of AR revenue, highlighting that enterprises are increasingly leveraging AR for operational applications such as training, remote assistance, simulation and real-time decision support.

Crucially, these systems speak natural language. A guard can ask, “When was this area last patrolled?” and receive concise, evidence-backed answers or ask the system to replay the last suspicious approach and mark it for later review. This moves wearables from passive recorders to active decision-support tools, increasing situational awareness while keeping hands and attention free.

While widespread adoption may still be a few years away, the trajectory is clear. The future of security work will be increasingly wearable – through smart glasses, headsets or other wrist-mounted devices – and powered by conversational, intelligent systems that deliver insights and decision support in real-time.

Conclusion — integrate, simulate, augment

Across these trends, the theme is consistent: AI is the enabler that makes previously hyped technologies operationally useful.

For CISOs, facility heads and operations leaders, the practical playbook for 2026 is simple and strategic: prioritise integration (open, auditable APIs), explore simulation capabilities (digital twins that map to SOPs), and pilot wearable augmentation where it reduces time-to-decision. Success is best measured through operational KPIs — response time, false-positive reduction and decision confidence — rather than novelty.

In simple terms, India’s security landscape is evolving quickly, and technologies like Agentic AI, Digital Twins and AR wearables are moving from early trials to real-world use. With national programmes such as Smart Cities Mission and Digital India accelerating modernisation, security leaders are prioritising AI for faster responses, digital twins for better planning, and wearables for stronger situational awareness on the ground. These tools are no longer experimental—they are becoming central to creating safer, more resilient security operations across the country.

After years of excitement and experimentation, we are entering a new era — one where emerging technology no longer feels like prototypes, but like partners.

We are now firmly in an era where these technologies move from promise to practice.

The post From Hype to Reality: The Three Forces defining Security in 2026 appeared first on ELE Times.