Збирач потоків

2026: A technology forecast for AI’s ever-evolving bag of tricks

Read on for our intrepid engineer’s latest set of predictions for the year(s) to come.

As has been the case the last couple of years, we’re once again flip-flopping what might otherwise seemingly be the logical ordering of this and its companion 2025 look-back piece. I’m writing this 2026 look-ahead for December publication, with the 2025 revisit to follow, targeting a January 2026 EDN unveil. While a lot can happen between now and the end of 2025, potentially affecting my 2026 forecasting in the process, this reordering also means that my 2025 retrospective will be more comprehensive than might otherwise be the case.

Without any further ado, and as usual, ordered solely in the cadence in which they initially came out of my cranium…

AI-based engineeringLikely unsurprisingly, as will also be the case with the subsequent 2025 retrospective-to-come, AI-related topics dominate my forecast of the year(s) to come. Take “vibe coding”, which entered the engineering and broader public vernacular only in February and quickly caught fire. Here’s Wikipedia’s introduction to the associated article on the subject:

Vibe coding is an artificial intelligence-assisted software development technique popularized by Andrej Karpathy in February 2025. The term was listed on the Merriam-Webster website the following month as a “slang & trending” term. It was named Collins Dictionary‘s Word of the Year for 2025.

Vibe coding describes a chatbot-based approach to creating software where the developer describes a project or task to a large language model (LLM), which generates code based on the prompt. The developer does not review or edit the code, but solely uses tools and execution results to evaluate it and asks the LLM for improvements. Unlike traditional AI-assisted coding or pair programming, the human developer avoids examination of the code, accepts AI-suggested completions without human review, and focuses more on iterative experimentation than code correctness or structure.

Sounds great, at least in theory, right? Just tell the vibe coding service and underlying AI model what you need your software project to do; it’ll as-needed pull together the necessary code snippets from both open-source and company-proprietary repositories all by itself. If you’re already a software engineer, it enables you to crank out more code even quicker and easier than before.

And if you’re a software or higher-level corporate manager, you might even be able to lay off (or at least pay grade-downscale) some of those engineers in the process. Therein explaining the rapid rollout of vibe coding capabilities from both startups and established AI companies, along with evaluations and initial deployments that’ll undoubtedly expand dramatically in the coming year (and beyond). What could go wrong? Well…

Advocates of vibe coding say that it allows even amateur programmers to produce software without the extensive training and skills required for software engineering. Critics point out a lack of accountability, maintainability, and the increased risk of introducing security vulnerabilities in the resulting software.

Specifically, a growing number of companies are reportedly discovering that any upfront time-to-results benefits incurred by AI-generated code end up being counterbalanced by the need to then reactively weed out resulting bugs, such as those generated by hallucinated routines when the vibe coding service can’t find relevant pre-existing examples (assuming the platform hasn’t just flat-out deleted its work, that is).

To that point, I’ll note that vibe coding, wherein not reviewing the resultant software line-by-line is celebrated, is an extreme variant of the more general AI-assisted programming technology category.

But even if a human being combs through the resultant code instead of just compiling and running it to see what comes out the other end, there’s still no guarantee that the coding-assistance service won’t have tapped into buggy, out-of-date software repositories, for example. And there’s always also the inevitable edge and corner cases that won’t be comprehended upfront by programmers relying on AI engines instead of their own noggins.

That all said, AI-based programming is already having a negative impact on both the job prospects for university students in the computer science curriculum and the degree-selection and pursuit aspirations of those preparing to go to college, not to mention (as already alluded to) the ongoing employment fortunes of programmers already in the job market.

And for those of you who are instead focused on hardware, whether that be chip- or board-level design, don’t be smug. There’s a fundamental reason, after all, why a few hours before I started writing this section, NVIDIA announced a $2B investment in EDA toolset and IP provider Synopsys.

Leveraging AI to generate optimized routing layouts for the chips on a PCB or the functional blocks on an IC is one thing; conventional algorithms have already been handling this for a long time. But relying on AI to do the whole design? Call me cynical…but only cautiously so.

Memory (and associated system) supply and pricesSpeaking of timely announcements, within minutes prior to starting to write this section (which, to be clear, was also already planned), I saw news that Micron Technology was phasing out its nearly 30-year old Crucial consumer memory brand so that it could redirect its not-unlimited fabrication capacity toward more lucrative HBM (high bandwidth memory) devices for “cloud” AI applications.

And just yesterday (again, as I’m writing these words), a piece at Gizmodo recommended to readers: “Don’t Build a PC Right Now. Just Don’t”. What’s going on?

Capacity constraints, that’s what. Remember a few years back, when the world went into a COVID-19 lockdown, and everyone suddenly needed to equip a home office, not to mention play computer games during off-hours?

Device sales, with many of them based on DRAM, mass storage (HDDs and/or SSDs), and GPUs, shot through the roof, and these system building blocks also then went into supply constraints, all of which led to high prices and availability limits.

Well, here we go again. Only this time, the root cause isn’t a pandemic; it’s AI. In the last few years’ worth of coverage on Apple, Google, and others’ device announcements, I’ve intentionally highlighted how much DRAM each smartphone, tablet, and computer contains, because it’s a key determinant of whether (and if so, how well) it can run on-device inference.

Now translate that analogy to a cloud server (the more common inference nexus) and multiply both the required amount and performance of memory by multiple orders of magnitude to estimate the demand here. See the issue? And see why, given the choice to prioritize either edge or datacenter customers, memory suppliers will understandably choose the latter due to the much higher revenues and profits for a given capacity of HBM versus conventional-interface DRAM?

Likely unsurprising to my readers, nonvolatile memory demand increases are pacing those of their volatile memory counterparts. Here again, speed is key, so flash memory is preferable, although to the degree that the average mass storage access profile can be organized as sequential versus random, the performance differential between SSDs and lower cost-per-bit HHDs (which, mind you, are also increasingly supply-constrained by ramping demand) can be minimized.

Another traditional workaround involves beefing up the amount of DRAM—acting as a fast cache—between the mass storage and processing subsystems, although per the prior paragraph it’s a particularly unappealing option this time around.

I’ve still got spare DRAM DIMMs and M.2 SSD modules, along with motherboards, cases, PSUs, CPUs, and graphics cards, and the like sitting around, left over from my last PC-build binge.

Beginning over the upcoming holidays, I plan to fire up my iFixit toolkits and start assembling ‘em again, because the various local charities I regularly work with are clearly going to be even more desperate than usual for hardware donations.

The same goes for smartphones and the like, and not just for fiscally downtrodden folks…brace yourselves to stick with the devices you’ve already got for the next few years. I suspect this particular constraint portion of the long-standing semiconductor boom-and-bust cadence will be with us even longer than usual.

Electricity rates and environmental impactsNot a day seemingly goes by without me hearing about at least one (and usually multiple) new planned datacenter(s) for one of the big names in tech, either being built directly by that company or in partnership with others, and financed at least in part by tax breaks and other incentives from the municipalities in which they’ll be located (here’s one recent example).

And inevitably that very same day, I’ll also see public statements of worry coming from various local, state, and national government groups, along with public advocacy organizations, all concerned about the environmental and other degrading impacts of the substantial power and water needs demanded by this and other planned “cloud” facilities (ditto, ditto, and ditto).

Truth be told, I don’t entirely “get” the municipal appeal of having a massive AI server farm in one’s own back yard (and I’m not alone). Granted, there may be a short-duration uptick in local employment from construction activity.

The long-term increase in tax revenues coming from large, wealthy tech corporations is an equally enticing Siren’s Song (albeit counterbalanced by the aforementioned subsidies). And what politician can’t resist proudly touting the outcome of his or her efforts to bring Alphabet (Google)/Amazon/Apple/ Meta/Microsoft/[insert your favorite buzzy company name here] to his or her district?

Regarding environmental impacts, however, I’ll “showcase” (for lack of a better word) one particularly egregious example: Elon Musk’s xAI Colossus 1 and 2 data centers in Memphis, Tennessee.

The former, a repurposed Electrolux facility, went online in September 2024, only 122 days after construction began. The latter, for which construction started this March, is forecasted, when fully equipped, to be the “First Gigawatt Datacenter In The World”. Sounds impressive, right? Well, there’s also this, quoting from Wikipedia:

At the site of Colossus in South Memphis, the grid connection was only 8 MW, so xAI applied to temporarily set up more than a dozen gas turbines (Voltagrid’s 2.5 MW units and Solar Turbines’ 16 MW SMT-130s) which would steadily burn methane gas from a 16-inch natural gas main. However, according to advocacy groups, aerial imagery in April 2025 showed 35 gas turbines had been set up at a combined 422 MW. These turbines have been estimated to generate about “72 megawatts, which is approximately 3% of the (TVA) power grid”. According to the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC), the higher number of gas turbines and the subsequent emissions requires xAI to have a ‘major source permit’, however, the emissions from the turbines are similar to the nearby large gas-powered utility plants.

In Memphis, xAI was able to sidestep some environmental rules in the construction of Colossus, such as operating without permits for the on-site methane gas turbines because they are “portable”. The Shelby County Health department told NPR that “it only regulates gas-burning generators if they’re in the same location for more than 364 days. In the neighborhood of South Memphis, poor air quality has given residents elevated asthma rates and lower life expectancy. A ProPublica report found that the cancer risk for those living in this area already have four times the risk of cancer than what the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) considers to be an acceptable risk. In November 2024, the grid connection was upgraded to 150 MW, and some turbines were removed.

Along with high electricity needs, the expected water demand is over five million gallons of water per day in “… an area where arsenic pollution threatens the drinking water supply.” This is reported by the non-profit Protect Our Aquifer, a community organization founded to protect the drinking water in Memphis. While xAI has stated they plan to work with MLGW on a wastewater treatment facility and the installation of 50 megawatts of large battery storage facilities, there are currently no concrete plans in place aside from a one-page factsheet shared by MLGW.

Geothermal powerSpeaking of the environment, the other night I watched a reality-calibrating episode of The Daily Show, wherein John Stewart interviewed Elizabeth Kolbert, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and staff writer at The New Yorker:

I say “calibrating” because it forced me to confront some uncomfortable realities regarding global warming. As regular readers may already realize, either to their encouragement or chagrin, I’m an unabashed believer in the following:

- Global warming is real, already here, and further worsening over time

- Its presence and trends are directly connected to human activity, and

- Those trends won’t automatically (or even quickly) stop, far from reversing course, even if that causational human activity ceases.

What I was compelled to accept after watching Stewart and Kolbert’s conversation, augmenting my existing opinion that human beings are notoriously short-sighted in their perspectives, frequently to their detriment (both near- and long-term), were conclusions such as the following:

- Expecting humans to willingly lower (or even flatline, versus constantly striving to upgrade) their existing standards of living for the long-term good of their species and the planet they inhabit is fruitless

- And given that the United States (where I live, therefore the innate perspective) is currently the world’s largest supplier of fossil fuel—specifically, petroleum and natural gas—energy sources, powerful lobbyists and other political forces will preclude serious consideration of and responses to global warming concerns, at least in the near term.

In one sense, those in the U.S. are not alone with their heads-in-the-sand stance. Ironically, albeit intentionally, the photo I included at the beginning of the prior section was of a coal-burning power plant in China.

That said, at the same time, China is also a renewable energy leader, rapidly becoming the world’s largest implementer of both wind and solar cell technology, both of which are now cheaper than fossil fuels for new power plant builds, even after factoring out subsidies. China also manufactures the bulk of the world’s lithium-based batteries, which enable energy storage for later use whenever the sun’s not shining and the wind’s not blowing.

To that latter point, though, while solar, wind, and many other renewable energy sources, such as tidal power, have various “green” attributes both in an absolute sense and versus carbon-based alternatives, they’re inconsistent in output over time. But there’s another renewable option, geothermal power, that doesn’t suffer from this impermanence, especially in its emerging “enhanced” variety. Traditional geothermal techniques were only limited-location relevant, with consequent challenges for broader transmission of any power generated, as Wikipedia explains:

The Earth’s heat content is about 1×1019 TJ (2.8×1015 TWh). This heat naturally flows to the surface by conduction at a rate of 44.2 TW and is replenished by radioactive decay at a rate of 30 TW. These power rates are more than double humanity’s current energy consumption from primary sources, but most of this power is too diffuse (approximately 0.1 W/m2 on average) to be recoverable. The Earth’s crust effectively acts as a thick insulating blanket which must be pierced by fluid conduits (of magma, water or other) to release the heat underneath.

Electricity generation requires high-temperature resources that can only come from deep underground. The heat must be carried to the surface by fluid circulation, either through magma conduits, hot springs, hydrothermal circulation, oil wells, drilled water wells, or a combination of these. This circulation sometimes exists naturally where the crust is thin: magma conduits bring heat close to the surface, and hot springs bring the heat to the surface.

To bolster the identification of such naturally geothermal-friendly locations (the photo at the beginning of this section was taken in Iceland, for example), companies such as Zanskar are (cue irony) using AI to locate previously unknown hidden sources. I’m admittedly also pleasantly surprised that the U.S. Department of Energy just announced geothermal development funding.

And, to even more broadly deploy the technology, other startups like Fervo Energy and Quaise Energy are prototyping ultra-deep drilling techniques first pioneered with (again, cue irony) fracking to pierce the crust and get to the constant-temperature, effectively unlimited energy below it, versus relying on the aforementioned natural conduit fractures. That it can be done doesn’t necessarily mean that it can be done cost-effectively, mind you, but I for one won’t ever underestimate the power of human ingenuity.

World models (and other LLM successors)While the prior section focused on accepting the reality of ongoing AI technology adoption and evolution, suggesting one option (of several; don’t forget about nuclear fusion) for powering it in an efficient and environmentally responsible manner, this concluding chapter is in some sense a counterpoint. Each significant breakthrough to date in deep learning implementations, while on the one hand making notable improvements in accuracy and broader capabilities, has also demanded ever-beefier compute, memory, and other system resources to accomplish its objectives…all of which require more energy to power them, along with more water to remove the heat byproduct of this energy consumption. The AI breakthrough introduced in this section is no exception.

Yann LeCun, one of the “godfathers” of AI whom I’ve mentioned here at EDN numerous times before (including just one year ago), has publicly for several years now been highly critical of what he sees as the inherent AGI (artificial general intelligence) and other limitations of LLMs (large language models) and their transformer network foundations.

A recent interview with LeCun published in the Wall Street Journal echoed many of these longstanding criticisms, adding a specific call-out for world models as their likely successor. Here’s how NVIDIA defines world models, building on my earlier description of multimodel AI:

World models are neural networks that understand the dynamics of the real world, including physics and spatial properties. They can use input data, including text, image, video, and movement, to generate videos that simulate realistic physical environments. Physical AI developers use world models to generate custom synthetic data or downstream AI models for training robots and autonomous vehicles.

Granted, LeCun has no shortage of detractors, although much of the criticism I’ve seen is directed not at his ideas in and of themselves but at his claimed tendency to overemphasize his role in coming up with and developing them at the expense of other colleagues’ contributions.

And granted, too, he’s planning on departing Meta, where he’s managed Facebook’s Artificial Intelligence Research (FAIR) unit for more than a decade, for a world model-focused startup. That said, I’ll forever remember witnessing his decade-plus back live demonstration of early CNN (convolutional neural network)-based object recognition running on his presentation laptop and accelerated on a now-archaic NVIDIA graphics subsystem:

He was right then. And I’m personally betting on him again.

Happy holidays to all, and to all a good nightI wrote the following words a couple of years ago and, as was also the case last year, couldn’t think of anything better (or even different) to say this year, given my apparent constancy of emotion, thought, and resultant output. So, once agai,n with upfront apologies for the repetition, a reflection of my ongoing sentiment, not laziness:

I’ll close with a thank-you to all of you for your encouragement, candid feedback and other manifestations of support again this year, which have enabled me to once again derive an honest income from one of the most enjoyable hobbies I could imagine: playing with and writing about various tech “toys” and the foundation technologies on which they’re based. I hope that the end of 2025 finds you and yours in good health and happiness, and I wish you even more abundance in all its myriad forms in the year to come. Let there be Peace on Earth.

p.s…let me (and your fellow readers) know in the comments not only what you think of my prognostications but also what you expect to see in 2026 and beyond!

—Brian Dipert is the Principal at Sierra Media and a former technical editor at EDN Magazine, where he still regularly contributes as a freelancer.

Related Content

- 2025: A technology forecast for the year ahead

- 2024: A technology forecast for the year ahead

- 2023: A technology forecast for the year ahead

- 2022 tech themes: A look ahead

- A tech look back at 2022: We can’t go back (and why would we want to?)

- A 2021 technology retrospective: Strange days indeed

The post 2026: A technology forecast for AI’s ever-evolving bag of tricks appeared first on EDN.

Студент КПІ ім. Ігоря Сікорського у складі збірної України на Air Force and Marine Corps Trials!

Air Force and Marine Corps Trials - міжнародні змагання, які є відбірковим турніром до всесвітніх Warrior Games в США. Warrior Games - мультиспортивні змагання, які об’єднують поранених або травмованих військових і ветеранів із різних держав.

Gray codes: Fundamentals and practical insights

Gray codes, also known as reflected binary codes, offer a clever way to minimize errors when digital signals transition between states. By ensuring that only one bit changes at a time, they simplify hardware design and reduce ambiguity in applications ranging from rotary encoders to error correction.

This article quickly revisits the fundamentals of Gray codes and highlights a few practical hints engineers can apply when working with them in real-world circuits.

Understanding reflected binary (Gray) code

The reflected binary code (RBC), more commonly known as Gray code after its inventor Frank Gray, is a systematic ordering of binary numbers designed in a way that each successive value differs from the previous one in only a single bit. This property makes Gray code distinct from conventional binary sequences, where multiple bits may flip simultaneously during transitions.

To illustrate, consider the decimal values 1 and 2. In standard binary, they are represented as 001 and 010, requiring two bits to change when moving from one to the other. In Gray code, however, the same values are expressed as 001 and 011, ensuring that only one bit changes during the increment. This seemingly small adjustment has significant practical implications: it reduces ambiguity and minimizes the risk of misinterpretation during state changes.

Gray codes have long been valued in engineering practice. They help suppress spurious outputs in electromechanical switches, where simultaneous bit changes could otherwise produce transient errors. In modern applications, Gray coding also supports error reduction in digital communication systems. By simplifying logic operations and constraining transitions to a single bit, Gray codes provide a robust foundation for reliable digital design.

Gray code vs. natural binary

Unlike standard binary encoding, where multiple bits may change during a numerical increment, Gray code ensures that only a single bit flips between successive values. This one-bit transition minimizes ambiguity during state changes and enables simple error detection: if more than one bit changes unexpectedly, the system can flag the data as invalid.

This property is especially useful in position encoders and digital control systems, where transient errors from simultaneous bit changes can lead to misinterpretation. The figure below compares the progression of values in natural binary and Gray code, highlighting how Gray code preserves single-bit transitions across the sequence.

Figure 1 Table compares Gray code and natural binary sequences, highlighting single-bit transitions between increments. Source: Author

When it comes to reliability in absolute encoder outputs, Gray code is the preferred choice because it prevents data errors that can arise with natural binary during state transitions. In natural binary, a sluggish system response may momentarily misinterpret a change; for instance, the transition from 0011 to 0100 could briefly appear as 0111 if multiple bits switch simultaneously. Gray code avoids this issue by ensuring that only one bit changes at a time, making the output stream inherently more reliable and easier for controllers to validate in practice.

Furthermore, converting Gray code back to natural binary is straightforward and can be done quickly on paper. Begin by writing down the Gray code sequence and copying the leftmost bit directly beneath it. Then, add this copied bit to the next Gray code bit to the right, ignoring any carries, and place the result beside the first copied digit. Continue this process step by step across the sequence until all bits have been converted. The final row represents the equivalent natural binary value.

For example, consider the Gray code 1011.

- Copy the leftmost bit → binary begins as 1.

- Next, add (XOR) the copied bit with the next Gray bit: 1 XOR 0 = 1 → binary becomes 11.

- Continue: 1 XOR 1 = 0 → binary becomes 110.

- Finally: 0 XOR 1 = 1 → binary becomes 1101.

Thus, the Gray code 1011 corresponds to the natural binary value 1101.

Gray code 1011 is not a standard weighted code, yet in a 4‑bit sequence, it corresponds to the decimal value 13. Its natural binary equivalent, 1101, also evaluates to 13, as shown below:

(1×23) + (1×22) + (0x21) + (1×20) = 8 + 4 + 0 + 1 = 13

Since both representations yield the same decimal result, the conversion is verified as correct.

Figure 2 Table demonstrates step‑by‑step conversion of Gray code 1011 into its natural binary equivalent 1101. Source: Author

Gray code output in rotary encoders

The real difference in a Gray code encoder lies in its output. Instead of returning a binary number that directly reflects the rotor’s position, the encoder produces a Gray code value.

As discussed earlier, Gray code differs fundamentally from binary: it’s not a weighted number system, where each digit consistently contributes to the overall value. Rather, it is an unweighted code designed so that only one bit changes between successive states.

In contrast, natural binary often requires multiple bits to flip simultaneously when incrementing or decrementing, which can introduce ambiguity during transitions. In extreme cases, this ambiguity may cause a controller to misinterpret the encoder’s position, leading to errors in system response. By limiting changes to a single bit, Gray code minimizes these risks and ensures more reliable state detection.

Shown below is a 4-bit Gray code output rotary encoder. As can be seen, it has four output terminals labeled 1, 2, 4, and 8, along with a Common terminal. The numbers 1-2-4-8 represent the bit positions in a 4-bit code, with each terminal corresponding to one output line of the encoder. As the rotor turns, each line switches between high and low according to the Gray code sequence, producing a unique 4-bit pattern for every position.

Figure 3 Datasnip shows terminal ID of the 25LB22-G-Z 4-bit Gray code encoder. Source: Grayhill

The Common terminal serves as the reference connection—typically ground or supply return—against which the four output signals are measured. Together, these terminals provide the complete Gray code output that can be read by a controller or logic circuit to determine the encoder’s angular position.

Sidenote: Hexadecimal output encoders

While many rotary encoders provide Gray code or binary outputs, some devices are designed to deliver signals in hexadecimal format. In these encoders, the rotor position is represented by a 4-bit binary word that maps directly to hexadecimal digits (0–F). This approach simplifies integration with digital systems that already process data in hex, such as microcontrollers or diagnostic interfaces.

Unlike Gray code, hexadecimal outputs do not guarantee single-bit transitions between states, so they are more prone to ambiguity during mechanical switching. However, they remain useful in applications where compact representation and straightforward decoding outweigh the need for transition reliability.

Microcontroller decoding of Gray code

There are several ways to decode Gray codes, but the most common way today is to feed the output bits into a microcontroller and let software handle the counting. In practice, the program reads the signals from the rotary encoder through I/O ports and first converts the Gray code into a binary value. That binary value is then translated into binary-coded decimal (BCD), which provides a convenient format for driving digital displays.

From there, the microcontroller can update a seven-segment display, LCD, or other interface to present the rotor’s position in a clear decimal form. This software-based approach not only simplifies hardware design but also offers flexibility to scale with higher-resolution encoders or integrate additional processing features.

On a personal note, my first experiment with a Gray code encoder involved decoding the outputs using hardware logic circuits rather than software.

This post has aimed to peel back a few layers of Gray codes, offering both context and clarity. Of course, there is much more to explore—and those deeper dives will come in time. For now, I invite you to share your own experiences, insights, or questions about Gray codes in the comments. Your perspectives can spark the next layer of discussion and help shape future explorations.

T. K. Hareendran is a self-taught electronics enthusiast with a strong passion for innovative circuit design and hands-on technology. He develops both experimental and practical electronic projects, documenting and sharing his work to support fellow tinkerers and learners. Beyond the workbench, he dedicates time to technical writing and hardware evaluations to contribute meaningfully to the maker community.

T. K. Hareendran is a self-taught electronics enthusiast with a strong passion for innovative circuit design and hands-on technology. He develops both experimental and practical electronic projects, documenting and sharing his work to support fellow tinkerers and learners. Beyond the workbench, he dedicates time to technical writing and hardware evaluations to contribute meaningfully to the maker community.

Related Content

- Gray Code Fundamentals – Part 1

- Gray Code Fundamentals – Part 2

- Gray Code Fundamentals – Part 3

- Logic 101 – Part 4 – Gray Codes

- Gray Code Fundamentals – Part 5

The post Gray codes: Fundamentals and practical insights appeared first on EDN.

European firm orders two Riber MBE 6000 production systems

India’s Electronic Exports grow sixfold from ₹1.9 lakh crore to ₹11.3 lakh crore in a decade: Ashiwini Vaishnaw

Sh Ashwini Vaishnaw, Union Minister for Railways, Electronics, and Information Technology, took to his Twitter handle to underline India’s stride in the electronic exports. He points toward India’s ongoing transformation into a global electronics export hub driven by the sharp growth in production, jobs, and investments flowing into the sector, bolstered by various initiatives under the central government, including Make in India, PLI, ECMS, etc.

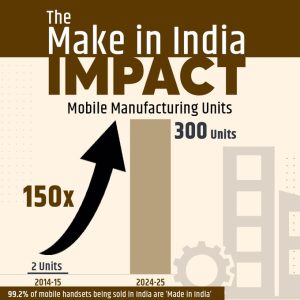

He writes, “ India’s growth story in electronics manufacturing is PM @narendramodi Ji’s vision of developing a comprehensive ecosystem.” He underlines the government’s continuity and effective oversight over the industry, which is leading to sustained development as well as growing impact on the nation and the world. The image he posted shows how the Make in India initiative has brought about a multiplication in the number of Mobile manufacturing units, from 2 in 2014-15 to 300 in 2024-25.

Electronics: Among the top 3 export categories

For India, out of the total electronics production worth Rs 11.3 Lakh crore in 2024-25, a strikingly high value of Rs 3.3 Lakh crores is attributed to exports, making electronics rank among the top 3 items exported by India. This also marks an eightfold increase in the export of the electronics item in the year 2024-25, rising from 0.38 Lakh crore in 2014-25.

Building Capacity for Modules, Equipment

He writes, “ Initial focus on finished products. Now we are building capacity for modules, components, sub-modules, raw materials, and the machines that make them.” He even goes on to add about the Electronics Component Manufacturing Scheme, wherein he talks about attracting 249 applications received amounting to ₹1.15 lakh crore investment, ₹10.34 lakh crore production, and creating 1.42 lakh jobs. He writes, “It is the highest-ever investment commitment in India’s electronics sector. This shows industry confidence.”

He also touched upon the Production-Linked Incentive (Large Scale Manufacturing-LSM), which enabled the industry to attract over ₹13,475 crore worth of investment. It is equivalent to a Production value of ~₹9.8 lakh crore. He even adds, “ Electronics manufacturing created 25 lakh jobs in the last decade. This is the real economic growth at the grassroots level. As we scale semiconductors and component manufacturing, job creation will accelerate.”

“From finished products to components, production is growing. Exports are rising. Global players are confident. Indian companies are competitive. Jobs are being created,” writes the minister as he shares India’s Make In India Impact Story.

The post India’s Electronic Exports grow sixfold from ₹1.9 lakh crore to ₹11.3 lakh crore in a decade: Ashiwini Vaishnaw appeared first on ELE Times.

Fraunhofer IAF and Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy provide low-noise amplifiers for ALMA radio telescope array

Micro-LED reaches make-or-break phase as first production lines ramp at AUO

Виставка витинанок: від мороку – до світла перемоги

Колекція витинанок "Джерело світла", виготовлених учнями Дитячої школи мистецтв №5 Оболонського району (керівниця майстерні – Юлія Підкурганна), демонструється в ДПМ. "Ажурний лабіринт з робіт, створений під час війни і покликаний віддзеркалити і врівноважити асиметрію сил – тимчасову потворну асиметрію. Живий, динамічний експеримент, як в технічному, так і в ідейному розумінні, що розкриває пошарово сенси і підтексти" – так охарактеризували експозицію фахівці.

Co-packaged optics market to grow at 37% CAGR to $20bn by 2036

PlayNitride to acquire Lumiode

Voltage drop across Germanium Diode (1N60) in forward bias

| submitted by /u/SpecialistRare832 [link] [comments] |

Weekly discussion, complaint, and rant thread

Open to anything, including discussions, complaints, and rants.

Sub rules do not apply, so don't bother reporting incivility, off-topic, or spam.

Reddit-wide rules do apply.

To see the newest posts, sort the comments by "new" (instead of "best" or "top").

[link] [comments]

I designed a CH32V003 Compute Module

| Hi that's a CH32V003 Compute Module i design some time ago, nice specs with 48 MHz clock and tiny for a 2k flash product; Regard Jean-François [link] [comments] |

I just had to check Gemini AI to see whether it was as 'good' as the rest at electronics.

| Yep! Here's a low voltage DC to low voltage AC inverter courtesy of Gemini: [link] [comments] |

Нова навчально-наукова лабораторія протезування, медичної реабілітації та ерготерапії в КПІ ім. Ігоря Сікорського

🦾🦿 Навчально-наукова лабораторія протезування, медичної реабілітації та ерготерапії дозволяє проводити натурне моделювання верхніх та нижніх кінцівок з наступним виготовленням куксоприймальних гільз (куксоприймачів) протезів.

I built my own low-power binary wristwatch!

| Hey everyone! This is qron0b! A low-power binary wristwatch that I built every part of it myself, from the PCB to the firmware to the mechanical design. Check out the Github repo (don't forget to leave a star!): https://github.com/qewer33/qron0b The watch itself is rather minimalistic, it displays the time in BCD (Binary Coded Decimal) format when the onboard button is pressed. It also allows you to configure the time using the button. The PCB is designed in KiCAD and has the following components:

The firmware is written in bare-metal AVR C and is around ~1900 bytes meaning it fits the 2KB flash memory of the ATtiny24A. It was quite a fun challenge to adhere to the 2KB limit and I am working on further optimizations to reduce code size. The 3D printed case is designed in FreeCAD and is a screwless design. The top part is printed with an SLA printer since it needs to be translucent. I ordered fully transparent prints from JLCPCB and I'm waiting for them to arrive but for now, it looks quite nice in translucent black too! This was my first low-power board design and I'm quite happy with it, it doesn't drain the CR2032 battery too much and based on my measurements and calculations it should last a year easily without a battery replacement. [link] [comments] |

Crowbar circuits: Revisiting the classic protector

Crowbar circuits have long been the go-to safeguard against overvoltage conditions, prized for their simplicity and reliability. Though often overshadowed by newer protection schemes, the crowbar remains a classic protector worth revisiting.

In this quick look, we will refresh the fundamentals, highlight where they still shine, and consider how their enduring design continues to influence modern power systems.

Why “crowbar”?

The name comes from the vivid image of dropping a metal crowbar across live terminals to force an immediate short. That is exactly what the circuit does—when an overvoltage is detected, it slams the supply into a low-resistance state, tripping a fuse or breaker and protecting downstream electronics. The metaphor stuck because it captures the brute-force simplicity and fail-safe nature of this classic protection scheme.

Figure 1 A crowbar protection circuit responds to overvoltage by actively shorting the power supply and disconnecting it to protect the load from damage. Source: Author

Crowbars in the CRT era: When fuses took the fall

In the era of bulky cathode-ray tube (CRT) televisions, power supply reliability was everything. Designers knew that a single regulator fault could unleash destructive voltages into the horizontal output stage or even the CRT itself. The solution was elegantly brutal: the crowbar circuit. Built around a thyristor or silicon-controlled rectifier (SCR), it sat quietly until the supply exceeded the preset threshold.

Then, like dropping a literal crowbar across the rails, it slammed the output into a dead short, blowing the fuse and halting operation in an instant. Unlike softer clamps such as Zener diodes or metal oxide varistors, the crowbar’s philosophy was binary—either safe operation or total shutdown.

For service engineers, this protection often meant the difference between replacing a fuse and replacing an entire deflection board. It was a design choice that reflected the pragmatic toughness of the CRT era: it’s better to sacrifice a fuse than a television.

Beyond CRT televisions, crowbar protection circuits find application in vintage computers, test and measurement instruments, and select consumer products.

Crowbar overvoltage protection

A crowbar circuit is essentially an overvoltage protection mechanism. It remains widely used today to safeguard sensitive electronic systems against transients or regulator failures. By sensing an overvoltage condition, the circuit rapidly “crowbars” the supply—shorting it to ground—thereby driving the source into current limiting or triggering a fuse or circuit breaker to open.

Unlike clamp-type protectors that merely limit voltage to a safe threshold, the crowbar approach provides a decisive shutdown. This makes it particularly effective in systems where even brief exposure to excessive voltage can damage semiconductors, memory devices, or precision analog circuitry. The simplicity of the design, often relying on a silicon-controlled rectifier or triac, ensures fast response and reliable action without adding significant cost or complexity.

For these reasons, crowbar protection continues to be a trusted safeguard in both legacy and modern designs—from consumer electronics to laboratory instruments—where resilience against unpredictable supply faults is critical.

Figure 2 Basic low-power DC crowbar illustrates circuit simplicity. Source: Author

As shown in Figure 2, an overvoltage across the buffer capacitor drives the Zener diode into conduction, triggering the thyristor. The capacitor is then shorted, producing a surge current that blows the local fuse. Once latched, the thyristor reduces the rail voltage to its on-state level, and the sustained current ensures safe disconnection.

Next is a simple practical example of a crowbar circuit designed for automotive use. It protects sensitive electronics if the vehicle’s power supply voltage, such as from a load dump or alternator regulation failure, rises above the safe setpoint. The circuit monitors the supply rail, and when the voltage exceeds the preset threshold, it drives a dead short across the rails. The resulting surge current blows the local fuse, shutting down the supply before connected circuitry can be damaged.

Figure 3 Practical automotive crowbar circuit protects connected device via local fuse action. Source: Author

Crowbar protection: SCR or MOSFET?

Crowbar protection can be implemented with either an SCR or a MOSFET, each with distinct tradeoffs.

An SCR remains the classic choice: once triggered by a Zener reference, it latches into conduction and forces a hard short across the supply rail until the local fuse opens. This rugged simplicity is ideal for high-energy faults, though it lacks automatic reset capability.

A MOSFET-based crowbar, by contrast, can be actively controlled to clamp or disconnect the rail when overvoltage is detected. It offers faster response and lower on-state voltage, which is valuable for modern low-voltage digital rails, but requires more complex drive circuitry and may be less tolerant of large surge currents.

Now I remember working with the LTM4641 μModule regulator, notable for its built-in N-channel overvoltage crowbar MOSFET driver that safeguards the load.

GTO thyristors and active crowbar protection

On a related note, gate turn-off (GTO) thyristors have also been applied in crowbar protection, particularly in high-power systems. Unlike a conventional SCR that latches until the fuse opens or power is removed, a GTO can be actively turned off through its gate, allowing controlled reset after an overvoltage event. This capability makes GTO-based crowbars attractive in industrial and traction applications where sustained shorts are undesirable.

Importantly, GTO thyristors enable “active” crowbars, in contrast to conventional SCRs that latch until power is removed. That is, an active crowbar momentarily shorts the supply during a transient, and gate-controlled turn-off then restores normal operation without intervention. In practice, asymmetric GTO (A-GTO) thyristors are preferred in crowbar protection, while symmetric (S-GTO) types see limited use due to higher losses.

However, their demanding gate-drive requirements and limited surge tolerance have restricted their use in low-voltage supplies, where SCRs remain dominant and MOSFETs or IGBTs now provide more practical and controllable alternatives.

Figure 4 A fast asymmetric GTO thyristor exemplifies speed and strength for demanding power applications. Source: ABB

A wrap-up note

Crowbar circuits may be rooted in classic design, but their relevance has not dimmed. From safeguarding power supplies in the early days of solid-state electronics to standing guard in today’s high-density systems, they remain a simple yet decisive protector. Revisiting them reminds us that not every solution needs to be complex—sometimes, the most enduring designs are those that do one job exceptionally well.

As engineers, we often chase innovation, but it’s worth pausing to appreciate these timeless building blocks. Crowbars embody the principle that reliability and clarity of purpose can outlast trends. Whether you are designing legacy equipment or modern platforms, the lesson is the same: protection is not an afterthought, it’s a foundation.

I will close for now, but there is more to explore in the enduring story of circuit protection. Stay tuned for future posts where we will continue connecting classic designs with modern challenges.

T. K. Hareendran is a self-taught electronics enthusiast with a strong passion for innovative circuit design and hands-on technology. He develops both experimental and practical electronic projects, documenting and sharing his work to support fellow tinkerers and learners. Beyond the workbench, he dedicates time to technical writing and hardware evaluations to contribute meaningfully to the maker community.

T. K. Hareendran is a self-taught electronics enthusiast with a strong passion for innovative circuit design and hands-on technology. He develops both experimental and practical electronic projects, documenting and sharing his work to support fellow tinkerers and learners. Beyond the workbench, he dedicates time to technical writing and hardware evaluations to contribute meaningfully to the maker community.

Related Content

- SCR Crowbar

- Where is my crowbar?

- Crowbar Speaker Protection

- Overvoltage-protection circuit saves the day

- How to prevent overvoltage conditions during prototyping

The post Crowbar circuits: Revisiting the classic protector appeared first on EDN.

Does the cold of deep space offer a viable energy-harvesting solution?

I’ve always been intrigued by “small-scale” energy harvest where the mechanism is relatively simple while the useful output is modest. These designs, which may be low-cost but may also use sophisticated materials and implementations, often make creative use of what’s available, generating power on the order of about 50 milliwatts.

These harvesting schemes often have the first-level story of getting “a little something for almost nothing” until you look more deeply in the detail. Among the harvestable sources are incidental wind, heat, vibration, incremental motion, and even sparks.

The most recent such harvesting arrangement I saw is another scheme to exploit the thermal differential between the cold night sky and Earth’s warmer surface. The principle is not new at all (see References)—it has been known since the mid-18th century—but it returns in new appearances.

This approach, from the University of California at Davis, uses a Stirling engine as the transducer between thermal energy and mechanical/electrical energy, Figure 1. It was mounted on a flat metal plane embedded into the Earth’s surface for good thermal contact while pointing at the sky.

Figure 1 Nighttime radiative cooling engine operation. (A) Schematic of engine operation at night. Top plate radiatively couples to the night sky and cools below ambient air temperature. Bottom plate is thermally coupled to the ground and remains warmer, as radiative access to the night sky is blocked by the aluminum top plate. This radiative imbalance creates the temperature differential that drives the engine. (B) Downwelling infrared radiation from the sky and solar irradiance are plotted throughout the evening and into the night on 14 August 2023. These power fluxes control the temperature of the emissive top plate. The fluctuations in the downwelling infrared are caused by passing clouds, which emit strongly in the infrared due to high water content. (C) Temperatures of the engine plates compared to ambient air throughout the run. The fluctuations in the top plate and air temperature match the fluctuations in the downwelling infrared. The average temperature decreases as downwelling power decreases. (D) Engine frequency and temperature differential remain approximately constant. Temporary increases in downwelling infrared, which decrease the engine temperature differential, are physically manifested in a slowing of the engine.

Figure 1 Nighttime radiative cooling engine operation. (A) Schematic of engine operation at night. Top plate radiatively couples to the night sky and cools below ambient air temperature. Bottom plate is thermally coupled to the ground and remains warmer, as radiative access to the night sky is blocked by the aluminum top plate. This radiative imbalance creates the temperature differential that drives the engine. (B) Downwelling infrared radiation from the sky and solar irradiance are plotted throughout the evening and into the night on 14 August 2023. These power fluxes control the temperature of the emissive top plate. The fluctuations in the downwelling infrared are caused by passing clouds, which emit strongly in the infrared due to high water content. (C) Temperatures of the engine plates compared to ambient air throughout the run. The fluctuations in the top plate and air temperature match the fluctuations in the downwelling infrared. The average temperature decreases as downwelling power decreases. (D) Engine frequency and temperature differential remain approximately constant. Temporary increases in downwelling infrared, which decrease the engine temperature differential, are physically manifested in a slowing of the engine.

Unlike other thermodynamic cycles (such as Rankine, Brayton, Otto, or Diesel), which require phase changes, combustion, or pressurized systems, the Stirling engine can operate passively and continuously with modest temperature differences. This makes them especially suitable for demonstrating mechanical power generation using passive thermal heat from the surroundings and radiative cooling without the need for fuels or active control systems.

Most engines which use thermal differences first generate heat from some source to be used against the cooler ambient side. However, there’s nothing that says the warmer side can’t be at the ambient temperature while the other side is colder relative to the ambient one.

Their concept and execution are simple, which is always attractive. The Stirling engine (essentially a piston driving a flywheel), is put on a 30 × 30 centimeter flat-metal panel that acts as a heat-radiating antenna. The entire assembly sits on the ground outdoors at night; the ground acts as the warm side of the engine as the antenna channels the cold of space.

Under best-case operation, the system delivered about 400 milliwatts of electrical power per square meter, and was used to drive a small motor. That is about 0.4% efficiency compared to theoretical maximum. Depending on your requirements, that areal energy density is somewhere between not useful and useful enough for small tasks such as charging a phone or powering a small fan to ventilate greenhouses, Figure 2.

Figure 2 Power conversion analysis and applications of radiative cooling engine. (A) Mechanical power plotted against temperature differential for various cold plate temperatures (TC). (Error bars show standard deviation.). Solid lines represent potential power corresponding to different quality engines denoted by F, the West number. (B) Voltage sweep across the attached DC motor shows maximum power point for extraction of mechanical to electrical power conversion at various engine temperature differentials (note: typical passive sign convention for electrical circuits is used). Solid red lines are quadratic fits of the measured data points (colored circles). Inset shows the dc motor mounted to the engine. (C) Bar graph denotes the remaining available mechanical power and the electrical power extracted (plus motor losses) when the DC motor is attached. (D) Axial fan blade attachment shown along with the hot-wire anemometer used to measure air speed. (E) Air speed in front of the fan is mapped for engine hot and cold plate temperatures of 29°C and 7°C, respectively. White circles indicate the measurement points. (F) Maximum air speed (black dots) and frequency (blue dots) as a function of engine temperature differential. Shaded gray regions show the range of air speeds necessary to circulate CO2 to promote plant growth inside greenhouses and the ASHRAE-recommended air speed for thermal comfort inside buildings.

Of course, there are other considerations such as harvesting only at night (hmmm…maybe as a complement to solar cells?) are needing a clear sky with dry air for maximum performance. Also, the assembly is, by definition, fully exposed to rain, sun, and wind, which will likely shorten its operation life.

The instrumentation they used was also interesting, as was their thermal-physics analysis they did as part of the graduate-level project. The flywheel of the engine was not only an attention-getter, its inherent “chopping” action also made it easy to count motor revolutions using a basic light-source and photosensor arrangement. The analysis based on the thermal cycle of the Stirling engine concluded that its Carnot-cycle efficiency was about 13%.

This is all interesting, but where does it stand on the scale of viability and utility? On one side, it is a genuine source of mechanical and follow-up electrical energy at very low cost. But that is only under very limited conditions with real-world limitations.

I think this form of harvesting gets attention because, as I noted upfront, it offers some usable energy at little apparent cost. Further, it’s very understandable, requires exotic materials or components, and comes with dramatic visual of the Stirling engine and its flywheel. It tells a good story that gets coverage and likely those follow-on grants. They have also filed a provisional patent related to the work; I’d like to see the claims they make.

But when you look at its numbers closely and reality becomes clearer, some of that glamour fades. Perhaps it could be used for a one-time storyline in a “McGyver-like” TV show script where the hero improvises such a unit, uses it to charge a dead phone, and is able to call for help. Screenwriters out there, are you paying attention?

Until then, you can read their full, readable technical paper “Mechanical power generation using Earth’s ambient radiation” published in the prestigious journal Science Advances from the American Association for the Advancement of Science; it was even featured on their cover, Figure 3, proving The “free” aspects of this harvesting and its photo-friendly design really do get attention!

Figure 3 The harvesting innovation was considered sufficiently noteworthy to be featured as the cover and lead story of Science Advances.

What’s your view on the utility and viability of this approach? Do you see any strong, ongoing applications?

Related Content

- Nothing new about energy harvesting

- An energy-harvesting scheme that is nearly useless?

- Niche Energy Harvesting: Intriguing, Innovative, Probably Impractical

- Underwater Energy Harvesting with Data-Link Twist

- Clever harvesting scheme takes a deep dive, literally

- Tilting at MEMS Windmills for Energy Harvesting?

- Energy Harvesting Gets Really Personal

- Lightning as an energy harvesting source?

- What’s that?…A fuel cell that harvests energy from…dirt?

References

- Applied Physics Letters, “Nighttime electric power generation at a density of 50 mW/m2 via radiative cooling of a photovoltaic cell”

- Nature Photonics, “Direct observation of the violation of Kirchhoff’s law of thermal radiation”

The post Does the cold of deep space offer a viable energy-harvesting solution? appeared first on EDN.

📰 Газета "Київський політехнік" № 45-46 за 2025 (.pdf)

Вийшов 45-46 номер газети "Київський політехнік" за 2025 рік

Національна премія науковцям кафедри високотемпературних матеріалів та порошкової металургії

Президент України Володимир Зеленський вручив дипломи і почесні знаки Національної премії України імені Бориса Патона науковцям кафедри високотемпературних матеріалів та порошкової металургії Інституту матеріалознавства та зварювання ім. Є.О. Патона.

Лауреатами премії стали: