Збирач потоків

The Tomorrow for AI and India’s edge advantage

Courtesy: Qualcomm

Artificial intelligence is entering its next chapter, one that reshapes not only how computing works, but how people experience technology in their daily lives. Intelligence is no longer just a feature, but is being built directly into devices and woven into systems and experiences so that it becomes ambient and always present.

In this next chapter, AI runs everywhere — across smartphones, PCs, wearables, cars, industrial machines, robots and connected infrastructure. These systems will understand context and the physical world around them and adjust in real time to our needs. Intelligence will operate quietly alongside us — working in the background, responding instantly, adapting continuously and ultimately expanding what’s possible in productivity, creativity and learning.

This marks a fundamental shift in how humans interact with technology. The interfaces we’ve relied on for decades — screens, apps, menus — will matter less as intelligence becomes more natural and intuitive. We won’t have to tell our devices what to do because they will understand our intent, anticipate what we want and act on our behalf. Some devices will increasingly see what we see, hear what we hear, understand what we read and write. In many cases, AI will feel less like a tool and more like a trusted assistant — always available, always learning and designed around us.

As agentic AI assistants become more common, they will become your personal companion in your home, the workplace and your car — everywhere you go. For example, in India, smart glasses are already being used to make digital payments using voice commands or by scanning a QR code. In your car, your AI assistant will not only help you find the fastest route but can also manage your errands, make recommendations or answer questions about places of interest.

In industries, edge AI boxes are being used to improve decision-making and operational efficiency, including monitoring and optimising production processes in a manufacturing facility or better managing inventory in a retail store.

Making these experiences real requires a new architecture — one where intelligence is distributed seamlessly across every computing device from cloud to edge. Training and deep reasoning will continue to scale in the cloud. At the same time, immediacy, perception and personalisation, as well as ambient and physical AI, will happen on devices — closer to people and things.

“To realise this future, democratizing access to AI is essential. That requires competitive and efficient data centre technology, powerful on-device intelligence and advanced connectivity working together.”

India’s size, diversity, economic growth and digital momentum make it one of the most important countries for AI’s next chapter. With hundreds of millions of connected users, a vibrant developer ecosystem, and deep expertise across engineering and software, India is not simply adopting AI — it is helping define how AI can work for the world.

In agriculture, AI can help enable precision farming and natural resource optimisation. Access to healthcare can be improved by on-device screening and diagnostics, which extend care into clinics, homes,s and remote communities. AI will realise the vision of smart cities with intelligent traffic management, smart infrastructure, security, and more. And, AI-enabled devices, such as PCs, smartphones, and wearables, will make education more personalised and support continuous, lifelong learning. These are not abstract ideas; they are practical pathways to broader participation in the AI economy.

To realise this future, democratizing access to AI is essential. That requires competitive and efficient data centre technology, powerful on-device intelligence, and advanced connectivity working together. It also requires an ecosystem approach — bringing together industry, startups, academia, and policymakers to ensure innovation is trusted, accessible,e and sustainable.

At Qualcomm, we’ve been building toward this future — advancing high-performance, power-efficient, and heterogeneous computing, AI, and wireless technologies that enable intelligence everywhere. But no single company can define AI’s next chapter alone. Progress will come through collaboration, from aligning technology with real-world needs, and from ensuring the benefits of AI extend beyond early adopters to entire societies.

With the right choices, India can help shape a future where intelligence empowers people, accelerates opportunity, and reaches every community — setting an example the world can follow.

The post The Tomorrow for AI and India’s edge advantage appeared first on ELE Times.

Marvell and Mojo Vision to co-develop high-density micro-LED connectivity solutions

Posifa Technologies Introduces PVC4001-C MEMS Pirani Vacuum Transducer for Wide-Range Vacuum Measurement

Posifa Technologies has introduced its new PVC4001-C MEMS Pirani vacuum transducer, the latest device in the company’s PVC4000 series. Designed for cost-effective OEM integration, the transducer combines a MEMS thermal conduction sensor, measurement electronics, a microprocessor, and an onboard barometric pressure sensor in an ultra-compact PCB assembly with a connector-terminated wire harness.

Based on Posifa’s second-generation MEMS thermal conduction chip, the PVC4001-C operates on the principle that the thermal conductivity of gases is proportional to vacuum pressure. Its electronics and microprocessor amplify and digitise the sensor signal and provide output via an I²C interface. For applications requiring calibrated output, users can enter up to 10 pairs of calibration points, which are used by a built-in piecewise linearization algorithm.

The PVC4001-C is designed to deliver stable performance across changing operating conditions. A built-in temperature sensor supports a temperature compensation algorithm to offset changes in thermal conductivity caused by ambient temperature variation. In addition, a pulsed excitation scheme — in which the sensor is heated for about 100 ms and then turned off for one second — helps minimise drift due to self-heating in high vacuum, while also reducing power consumption for battery-powered instruments.

The device provides a measurement range from 0.001 Torr to 900 Torr (1.3*10-4 kPa to 120 kPa) with a response time of less than 200 ms. Because Pirani vacuum sensors typically lose resolution above 10 Torr, the PVC4001-C adds an onboard barometric pressure sensor that supports measurement from 10 Torr to 760 Torr with 5 % accuracy across that extended range. This combination makes the device especially well-suited for portable digital vacuum gauges and for leak detection in closed systems maintained under primary vacuum, including vacuum-insulated panels.

Additional features of the PVC4001-C include low power consumption, resistance to contamination, and an operating temperature range of -25 °C to +85 °C.

The post Posifa Technologies Introduces PVC4001-C MEMS Pirani Vacuum Transducer for Wide-Range Vacuum Measurement appeared first on ELE Times.

STMicroelectronics to support AI infrastructure demand with high-volume production of its industry-leading silicon photonics platform

STMicroelectronics is now entering high-volume production for its state-of-the-art silicon photonics-based PIC100 platform used by hyperscalers for optical interconnect for data centres and AI clusters. The 800G and 1.6T PIC100 transceivers enable higher bandwidth, lower latency, and greater energy efficiency as AI workloads surge.

“Following the announcement of its new silicon photonics technology in February 2025, ST is now entering high-volume production for leading hyperscalers. The combination of our technology platform and the superior scale of our 300 mm manufacturing lines gives us a unique competitive advantage to support the AI infrastructure super-cycle,” said Fabio Gualandris, President, Quality, Manufacturing & Technology, STMicroelectronics. “Looking ahead, we are planning and executing on capacity expansions to enable more than quadrupling of production by 2027. This fast expansion is fully underpinned by customers’ long-term capacity reservation commitments.”

“The data centre pluggable optics market continues to expand strongly, reaching $15.5 billion in 2025. We expect the market to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17% from 2025 through 2030, surpassing $34 billion by the end of the forecast period. In addition, co-packaged optics (CPO) will emerge as a rapidly growing segment, contributing more than $9 billion in revenue by 2030. Over the same period, the share of transceivers incorporating silicon photonics modulators is projected to increase from 43% in 2025 to 76% by 2030,” said Dr. Vladimir Kozlov, CEO and Chief Analyst at LightCounting. “ST’s leading silicon photonics platform, coupled with its aggressive capacity expansion plan, illustrates its capabilities to provide hyperscalers with secure, long-term supply, predictable quality, and manufacturing resilience.”

Upcoming PIC100 TSV Platform TechnologyAI infrastructure is experiencing unprecedented scaling, with cloud-optical interconnect performance becoming a critical bottleneck. Drawing on years of silicon photonics innovation, ST’s PIC100 platform provides state-of-the-art optical performance, including best-in-class silicon and silicon nitride waveguide losses (respectively as low as 0.4 and 0.5 dB/cm), advanced modulator and photodiode performance, as well as an innovative edge coupling technology.

In parallel with high-volume PIC100 production, ST is planning to introduce the next step in its silicon photonics technology roadmap: the PIC100 TSV, a new and unique platform that integrates through-silicon via (TSV) technology to further increase optical connectivity density, module integration, and system-level thermal efficiency. The PIC100 TSV platform is designed to support future generations of Near Packaged Optics (NPO) and co-packaged optics (CPO), aligning with hyperscalers’ long-term migration paths toward deeper optical–electronic integration for scale up.

The post STMicroelectronics to support AI infrastructure demand with high-volume production of its industry-leading silicon photonics platform appeared first on ELE Times.

Niobium capacitors as an alternative to tantalum capacitors

| submitted by /u/1Davide [link] [comments] |

My Smart Wall Clock

| I designed the case myself. Use esp32-c3 with WifiManager library. The time updates automatically:) [link] [comments] |

Just started the ICL7135-based multimeter

| Yes, I will try to build a precise voltage/current measurment equipment from scratch just for fun. Wish me luck. One step at a time: - 5-digit multiplexed display with the К176ИД2 driver - MC34063 negative rail DC-DC converter - 555 timer 120kHz click source - REF3333 precise voltage reference [link] [comments] |

University of Sheffield to lead £12.5m UK Centre for Heterogeneous Integrated MicroElectronic and Semiconductor Systems

Low-cost MCUs enable smarter embedded devices

Leveraging ST’s 40-nm process and an Arm Cortex-M33 core, STM32C5 MCUs deliver increased speed for cost-sensitive embedded devices. The microcontrollers run faster than many entry-level chips, improving the capabilities of compact smart devices in factories, homes, cities, and infrastructure while keeping dynamic power consumption low (<80 µA/MHz).

Running at 144 MHz and achieving a CoreMark score of 593, the Cortex-M33 offers up to three times the performance of typical Cortex-M0+ devices. ST’s 40-nm cost-efficient manufacturing process supports higher clock speeds and larger on-chip memory. The STM32C5 series integrates 128 KB to 1024 KB of flash and 64 KB to 256 KB of RAM.

The MCUs are designed to meet SESIP3 and PSA Level 3 security requirements, with memory protection, tamper protection, cryptographic engines, and temporal isolation to protect processes such as secure boot and firmware updates. Variants with additional security provide hardware unique key support, secure key storage, and hardware cryptographic accelerators for symmetric and asymmetric operations.

The STM32C5 MCUs are entering production now and are available in packages ranging from 20 to 144 pins. Pricing starts at $0.64 each in 10,000-unit quantities.

The post Low-cost MCUs enable smarter embedded devices appeared first on EDN.

TinyEngine NPU powers AI in TI MCUs

TI’s MSPM0G5187 and AM13E23019 MCUs integrate the TinyEngine NPU, enabling efficient edge AI in systems ranging from simple to complex. These latest additions to TI’s portfolio of AI-enabled hardware, software, and tools allow engineers to deploy intelligence anywhere. This announcement moves TI closer to its goal of integrating the TinyEngine NPU across its entire microcontroller lineup.

The MSPM0G5187 is powered by an Arm Cortex-M0+ 32-bit core operating at up to 80 MHz and includes 128 KB of flash. Its TinyEngine NPU is capable of running AI models with up to 90× lower latency and more than 120× less energy per inference than comparable MCUs without an accelerator. By performing neural-network computation locally, the NPU operates in parallel with the primary CPU running application code. Priced at under $1 in 1,000-unit quantities, the MSPM0G5187 brings edge AI to simpler, smaller, and lower-cost applications.

Aimed at real-time motor control, the AM13E23019 leverages an Arm Cortex-M33 32-bit core operating at up to 200 MHz and includes 512 KB of flash. It maintains precise real-time control loops for up to four motors while the TinyEngine NPU runs adaptive control algorithms. An integrated trigonometric math accelerator performs calculations 10× faster than coordinate rotation digital computer (CORDIC) implementations, enabling more responsive motor control.

The MSPM0G5187 is available now in production quantities on TI.com, while the AM13E23019 is currently available in preproduction quantities.

The post TinyEngine NPU powers AI in TI MCUs appeared first on EDN.

Edge AI SoC integrates tri-radio

The i.MX 93W applications processor from NXP combines a dedicated AI NPU with secure tri-radio wireless connectivity in a single package. By eliminating the need for up to 60 discrete components, the SoC reduces board area, design complexity, and system-level costs.

Purpose-built to accelerate physical AI deployment, the i.MX 93W is supported by NXP’s software stack, eIQ AI enablement tools, and precertified reference designs that simplify RF integration. The device integrates a dual-core Arm Cortex-A55 processor and an Arm Ethos NPU capable of up to 1.8 eTOPS. Wireless connectivity is provided by the IW610 tri-radio, supporting Wi-Fi 6, Bluetooth Low Energy, and IEEE 802.15.4 for Matter and Thread.

The i.MX 93W SoC integrates an EdgeLock Secure Enclave (Advanced Profile) to support device security and regulatory frameworks such as the European Cyber Resilience Act. The enclave provides a hardware root of trust for secure boot, updates, device attestation, and device access. With NXP’s EdgeLock 2GO key management service, devices can be provisioned during manufacturing or in the field.

The i.MX 93W is slated to begin sampling in the second half of 2026.

The post Edge AI SoC integrates tri-radio appeared first on EDN.

200-V MOSFETs cut conduction losses

Two devices have joined iDEAL Semiconductor’s SuperQ 200-V MOSFET portfolio, offering very low RDS(on) in standard power packages. These two SuperQ devices are designed for demanding motor-drive applications that require high efficiency, robustness, and fault tolerance.

The iS20M5R5S1T achieves a maximum RDS(on) of just 5.5 mΩ in the compact TOLL package, enabling higher power density and reduced conduction losses in space-constrained designs. Similarly, the iS20M6R3S1P delivers a maximum RDS(on) of 6.3 mΩ in the rugged TO-220 package, providing high efficiency for applications that favor through-hole assembly, mechanical mounting, or direct heatsinking.

The new SuperQ MOSFETs feature high short-circuit withstand current and closely matched gate thresholds, with a variation of ±0.5 V, for easier paralleling. They are rated for 175 °C and can handle currents up to 151 A in the TOLL package and 172 A in the TO-220 package. Both devices are avalanche-rated and undergo 100% UIS testing in production.

In addition to motor drives, these MOSFETs are also suitable for switched-mode power supplies, secondary-side synchronous rectification, and other high-current industrial or battery-powered systems.

The iS20M5R5S1T and iS20M6R3S1P are in volume production and available through iDEAL’s global distribution channels.

The post 200-V MOSFETs cut conduction losses appeared first on EDN.

Sfera Labs debuts industrial Raspberry Pi edge systems

Sfera Labs has introduced an industrial Raspberry Pi-based edge server and PLC for industrial IoT and edge applications. The Strato Pi Plus server and Iono Pi v3 controller come in DIN-rail enclosures with an embedded Raspberry Pi 4 or 5 single-board computer (SBC), delivering industrial-grade systems for automation, field communications, and IoT edge deployments that require continuous, unattended operation.

The Strato Pi Plus features a hybrid architecture that pairs the Raspberry Pi SBC with an RP2354 MCU. The RP2354 operates independently of the main processor to manage critical real-time functions and system supervision, including an independent hardware watchdog. In-field firmware updates for the RP2354 are supported via OTA, managed directly through the Raspberry Pi. Serial connectivity includes four individually opto-isolated RS-485 ports and one CAN FD interface. The Strato Pi Plus operates from an integrated 10–50 V DC supply with surge and reverse-polarity protection and a 3.3 A resettable fuse.

The Iono Pi v3 industrial PLC integrates a 9–28 V DC power supply, four power relays, high-resolution analog voltage and current inputs, and seven configurable GPIO pins. Like the Strato Pi Plus, it implements a hardware watchdog in the RP2354 MCU that operates independently of the Raspberry Pi SBC. The device also includes a real-time clock with a temperature-compensated oscillator and replaceable backup battery. An embedded Microchip ATECC608 secure element enables hardware-based authentication and cryptographic key storage.

A timeline for availability of the Strato Pi Plus and Iono Pi v3 was not provided at the time of this announcement.

The post Sfera Labs debuts industrial Raspberry Pi edge systems appeared first on EDN.

I built a text-to-schematic CLI tool

| There are a lot of "AI generates hardware" claims floating around, and most of them produce garbage. I've been working on a tool called boardsmith that I think does something actually useful, and I want to show what it really outputs rather than making abstract claims. Here's what happens when you run boardsmith build -p "ESP32 with BME280 temperature sensor, SSD1306 OLED, and DRV8833 motor driver" --no-llm: You get a KiCad 8 schematic with actual nets wired between component pins. The I2C bus has computed pull-up resistors (value based on bus capacitance with all connected devices factored in). Each IC has decoupling caps with values per the datasheet recommendations. The power section has a voltage regulator sized for the total current budget. I2C addresses are assigned to avoid conflicts. The schematic passes KiCad's ERC clean. You also get a BOM with JLCPCB part numbers (191 LCSC mappings), Gerber files ready for fab upload, and firmware that compiles for the target MCU. The ERCAgent automatically repairs ERC violations after generation. boardsmith modify lets you patch existing schematics ("add battery management") without rebuilding. And boardsmith verify runs 6 semantic verification tools against the design intent (connectivity, bootability, power, components, BOM, PCB). The tool has a --no-llm mode that's fully deterministic — no AI, no API key, no network. The synthesis pipeline has 9 stages and 11 constraint checks. It's computing the design, not asking a language model to guess at it. Where it falls short: 212 components in the knowledge base (covers common embedded parts, but you'll hit limits). No high-speed digital design — no impedance matching, no differential pairs. No analog circuits — no op-amp topologies, no filter design. Auto-placed PCB layout is a starting point, not a finished board. It's fundamentally a tool for the "boring" part of embedded design — the standard sensor-to-MCU wiring that experienced engineers can do in their sleep but still takes 30 minutes. Open source (AGPL-3.0), built by a small team at ForestHub.ai. I'd love feedback from people who actually design circuits — is this solving a real annoyance, or am I in a bubble? [link] [comments] |

CEA-Leti and NcodiN partner to industrialize 300mm silicon photonics for bandwidth-hungry AI interconnects

💎 Круглий стіл «Можливості Програми “Горизонт Європа” у 2026 році: відкриті конкурси та механізми участі»

«Офіс Горизонт Європа в Україні» НФДУ повідомляє, що 24 березня у Києві відбудеться круглий стіл «Можливості Програми “Горизонт Європа” у 2026 році: відкриті конкурси та механізми участі».

CCTV Controller - Running on a RP2040 Microcontroller using circuit python KMK firmware for switching between camera feeds

| I posted this a bit ago for the keyboard diode matrix I made. Please ignore the shoddy soldering on the prototype board lol. But this project has been my first dive into microcontrollers, and after watching some videos on how easy circuit python KMK firmware ( https://github.com/KMKfw/kmk\_firmware ) was to install and configure I just knew I had to do it. In essence this thing is just a clunky big macro board that I made as a proof of concept before I make a nicer one. The software it's intended to be used with is a bit of python that I used gemini / chatgpt to make ( https://github.com/IvoryToothpaste/rtsp-viewer ) that maps all the camera feeds to a specific hotkey via the config file. This thing was a lot of fun to make, and I'm excited to post the final version of everything :) [link] [comments] |

ROHM’s TRCDRIVE pack, HSDIP20 and DOT-247 silicon carbide molded power modules now available online

Impact of AI on Computing and the Criticality of Testing

Courtesy: Teradyne

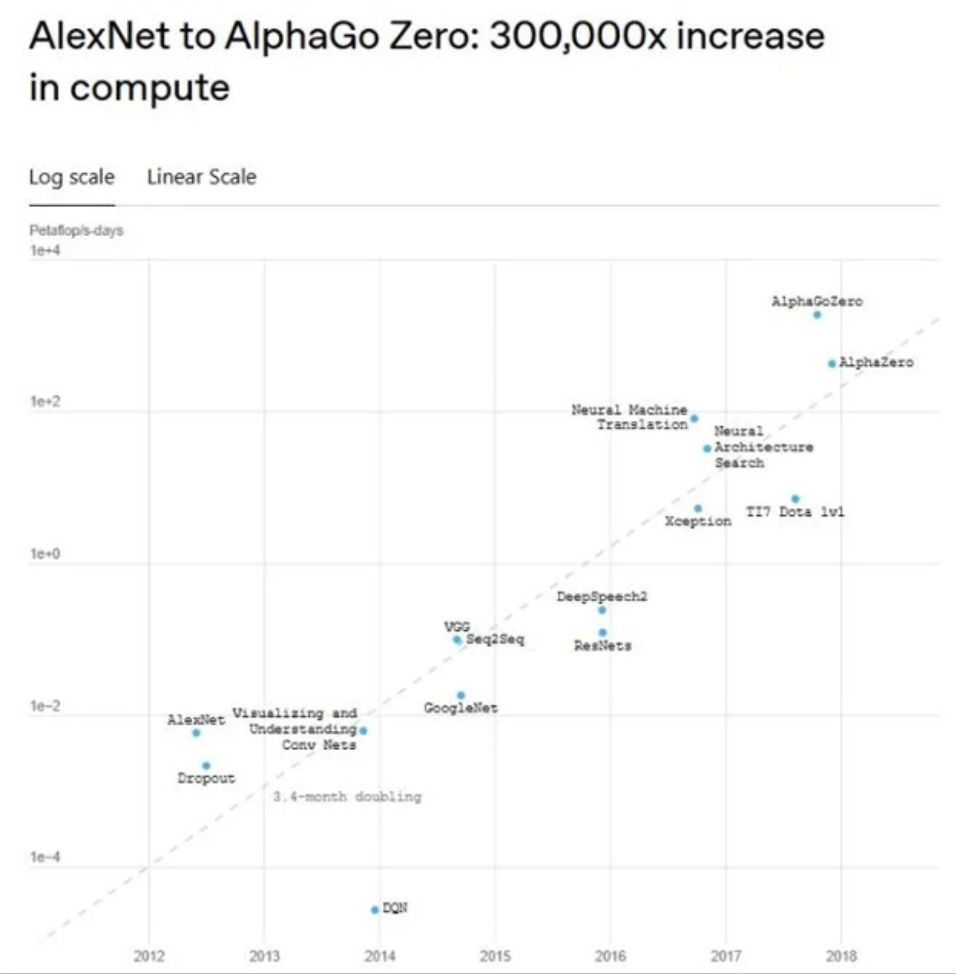

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming industries, enhancing our daily lives, and improving efficiency and decision-making, but its need for computing power is growing at an astonishing rate, doubling every three months (Figure 1). To maintain this pace, the semiconductor industry is moving beyond traditional chip development – it has entered the era of heterogeneous chiplets in advanced integrated packages.

(Figure 1: The Growth of Compute Requirements. Source: https://openai.com/index/ai-and-compute/)

(Figure 1: The Growth of Compute Requirements. Source: https://openai.com/index/ai-and-compute/)

The Rise of Chiplets

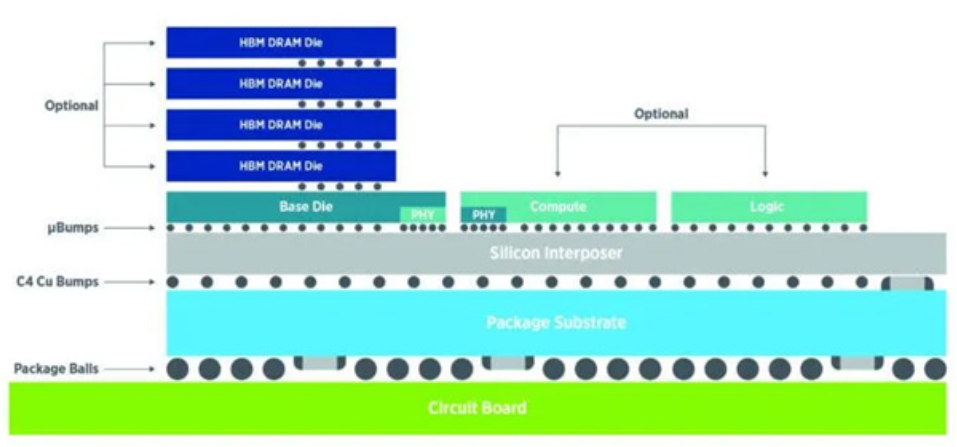

Chip companies like NVIDIA and AMD are rewriting the rules, designing architectures that combine multiple CPUs and GPUs in a single advanced package along with high bandwidth memory (HBM). AI workloads require rapid access to vast amounts of data, made possible by integrating HBMs. This approach, combining two, four, or more processing cores with HBM stacks, requires a complex, advanced packaging technique developed by TSMC called CoWos® – Chip-on-Wafer-on-Substrate, typically referred to as 2.5/3D packaging (Figure 2). These packages can exceed 100 mm x 100 mm in size and will require wafer interposer probers that can handle large CoW modules/stacks and also meet significantly larger thermal dissipation requirements, as discussed below.

(Figure 2: 2.5D/3D packaging architecture, Source: Teradyne)

(Figure 2: 2.5D/3D packaging architecture, Source: Teradyne)

To maintain peak performance, these heterogeneously integrated advanced packaging devices need proprietary high-speed interfaces to communicate efficiently. All these requirements contribute to an increasingly complex semiconductor landscape.

Testing Becomes More Complex in Step with Chip Advancements

As package complexity increases, so does the need for more deliberate test strategies. In the transition from monolithic dies to chiplets, long-established test methods are not always directly transferable because test IP is now distributed across multiple dies and, in some cases, across different design teams or companies. This fragmentation requires a clearer definition of what must be tested at each stage—die, bridge, interposer, substrate, and stack—and which standards or techniques apply to each scope.

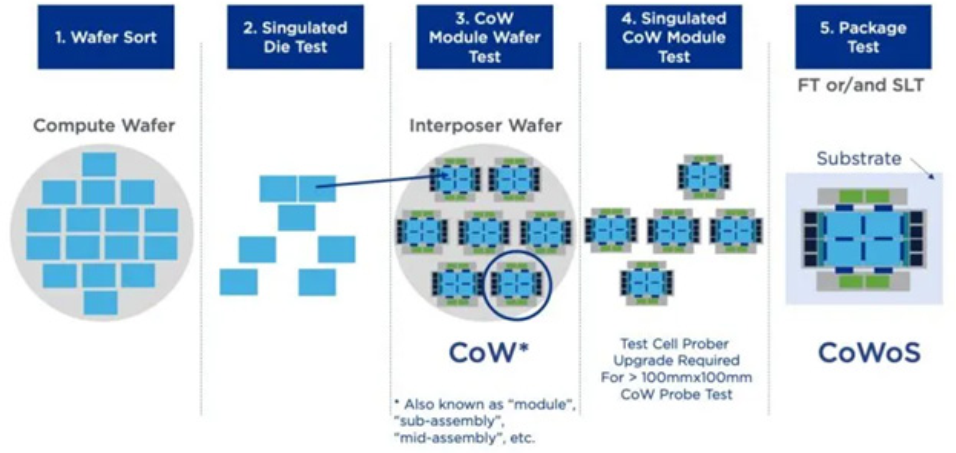

Packing multiple dies into a single chiplet-based system is a major advancement, but it raises a key challenge: verifying that every component functions correctly before final assembly. Multi-die packages require rigorous screening to avoid yield loss, and it is not enough to qualify only the dies. Interposers, substrates, bridges, and stacks also need to be validated, using test techniques appropriate to each layer. The industry is thus moving into “known-good-everything”, from known-good-die (KGD) to known-good-interposer (KGI), to known-good-CoW (KG-CoW), and so on. (Figure 3)

(Figure 3: Possible test insertions to ensure KGD and KG-CoW. Source: Teradyne)

(Figure 3: Possible test insertions to ensure KGD and KG-CoW. Source: Teradyne)

High-speed communication between chiplets introduces an additional layer of complexity. Dies must exchange data at extreme speeds – such as during GPU-to-HBM transfers – yet their physical and electrical interfaces vary by manufacturer. Open standards like Universal Chiplet Interconnect Express (UCIe ) continue to evolve, but chiplet interfaces still differ widely. To support this diversity, test solutions increasingly need interface IP that behaves like the device’s native protocol to avoid electrical overstress or probe-related damage. Some suppliers now offer UCIe-compliant PHY and controller IP that device makers can integrate, enabling automated test equipment (ATE) platforms to test high-speed links safely and consistently.

) continue to evolve, but chiplet interfaces still differ widely. To support this diversity, test solutions increasingly need interface IP that behaves like the device’s native protocol to avoid electrical overstress or probe-related damage. Some suppliers now offer UCIe-compliant PHY and controller IP that device makers can integrate, enabling automated test equipment (ATE) platforms to test high-speed links safely and consistently.

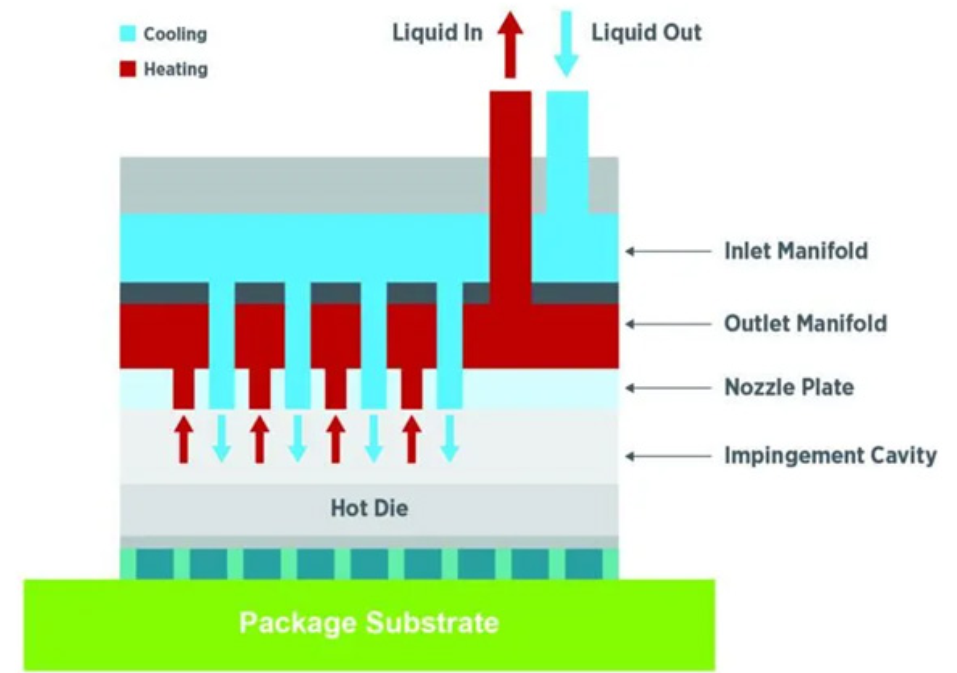

(Figure 4: Chip-level bare cooling, Source: Teradyne)

(Figure 4: Chip-level bare cooling, Source: Teradyne)

Manufacturers and test operators must also pay close attention to thermal management. More processing power means more heat dissipation issues, requiring advanced cooling methods – perhaps even liquid cooling inside the package itself (Figure 4). More die in the package means more connections, and thus, more resources are needed in the tester. More transistors mean higher power supply current requirements, more power supply instruments, and an increased set of thermal challenges that demand innovative cooling solutions and advanced adaptive thermal control (ATC) strategies.

Lastly, manufacturing test operations must consider the interposer, a physical interface layer that electrically connects a chip to a substrate or other active component. For example, a multilayer or 2.5D package includes multiple dies on an interposer assembled on top of a substrate. That interposer functions as a mini silicon board, routing signals from the upper floor die to the bottom floor die. It’s critical that the interposer is also a known good die or known good interposer (KGI) to ensure adequate yields for advanced packages.

The Future of AI and Semiconductor Testing

There has been an uptick in industry recognition that semiconductor testing is an integral part of today’s chiplet and advanced packaging trend. As this unfolds, AI computing will continue its pace of unprecedented evolution, relying on semiconductor testing to fill a crucial role in ensuring quality devices get to market in the shortened timelines today’s market demands. Semiconductor test will remain the unsung hero of AI-driven computing, steadily enabling the next wave of technological breakthroughs.

The post Impact of AI on Computing and the Criticality of Testing appeared first on ELE Times.

A long-ago blow leads to water overflow: Who could know?

Mechanical analogies to electronics symbols are common in other engineering disciplines. We might refer to this one, then, as akin to a battery with an internal short circuit?

I’ll warn you upfront that this particular blog post has nothing specific to do with electronics (aside, I suppose, from the potential for electrocution caused by a water-soaked calamity). That said, I’ll also postulate upfront that (IMHO, at least) it has a great deal to do with engineering in general, specifically as it exemplifies the edge and corner cases that were the subject of a 2.5+ year back previous post from yours truly. Read on or not, as you wish. That said, I hope you’ll proceed!

I kicked off that prior writeup with the following prose:

Whether or not (and if so, how) to account for rarely encountered implementation variables and combinations in hardware and/or software development projects is a key (albeit often minimized, if not completely overlooked) “bread and butter” aspect of the engineering skill set… I’ve always found case studies about such anomalies and errors fascinating, no matter that I’ve also found them maddening when I’m personally immersed in them!

Speaking of the personal angle…and immersion, for that matter…

At our peak, my wife and I have had (several times so far…blame me, not her) up to five four-legged mammal companions concurrently sharing our residence with us. Therein explaining the sizeable (4-gallon/15-liter reservoir) Petmate Aspen Pet Lebistro Cat and Dog Water Dispenser that we bought through Amazon at the beginning of 2020:

Amazon’s packaging robustness can be hit-and-miss; when this particular order arrived at our front door, the reservoir and base were detached and loose. And the outer box contained no packing material, far from inner boxes for either/both constituent piece(s). Unsurprisingly, therefore, the reservoir tank had a dent in one corner (the below is a more recent picture…keep reading):

I pushed it back into place as best I could:

and then filled-and-tested the tank, which still seemed to be watertight. And then, driven by a broader longstanding abhorrence for sending functionally sound albeit cosmetically compromised stuff to the landfill, I decided to keep it and press it into service, accompanied by a successful partial-refund request made to Amazon customer service.

Fast-forward six years. We’re down (for the moment, at least) to only one (canine) companion, a factoid which as you’ll soon see likely ended up being key. And we started finding puddles of standing water in proximity to the water dispenser on the (watertight vinyl, thankfully) laundry room floor. Did we initially accuse the dog of bumping into the dispenser, causing spills? Yes, we did. Did subsequent observation convince us that our initial theory was off base? Yes, it did. And did we then feel badly for unjustly initially blaming the dog? Yes…we did. Bad humans. Bad!

In-depth painstaking engineering analysis (cough) eventually led to the realization that the water spills were preceded by slow-but-sure filling of the bowl all the way to the lip (and then beyond, therefore the puddles), versus the inch-below-the-lip level that the dispenser traditionally stuck to. But what had changed? Figuring this out required that I first learn about how gravity water bowls function in the first place. How do they initially fill only to the inch-below-the-lip level, and how do they then automatically maintain this level as the water is consumed by canine and feline companions, until drained (if one of the humans had forgotten to refill it, that is)?

I learned the answer from, as I’m more generally finding of late, Reddit. Specifically, from a post in the cleverly named “Explain Like I’m Five” subreddit (I’m doing my best not to take offense) titled “How do self-filling/gravity fed pet water bowls not overflow and spill everywhere?”. The entire discussion thread is fascinating, again IMHO, containing exchanges such as the following:

- ender42y: This works for a stack up to 32 ft or 9 meters tall (at standard atmospheric pressure) at which point the top of the water tank would actually start to form a vacuum.

- bloc97: It is a bit shorter in practice as the water will start to boil at ~2 kpa (assuming 20c).

- MindStalker: That’s exactly why you are limited to a column that’s about 9 meters tall, anything above that boils away.

- bloc97: Yes, as there are two processes that determines the column height (density and vapor pressure of the fluid), we just need to make sure not to confuse the two.

Again:  . That said, have I yet admitted what a devoted follower of the TV personality Mr. Wizard I was as a wee lad (we didn’t have YouTube back then)?

. That said, have I yet admitted what a devoted follower of the TV personality Mr. Wizard I was as a wee lad (we didn’t have YouTube back then)?

That admission explains (more than) a few things, yes? Speaking of vacuums, here’s the “money quote” from that Reddit post thread, with kudos to Redditor nestcto:

Recapping the basics, the opening acts as both the exit for the water, and the entrance for air. The air is obviously needed because under normal circumstances, you can’t just have nothing in the bottle. The water must be replaced with something. That’s where the air comes in.

So making the water leave the bottle is easy. You just have to make sure the water is creating more outward pressure to leave the bottle, than the vacuum inside trying to replace it with air.

To keep the water in, you have to make sure the water can’t create more pressure to leave the bottle than the vacuum trying to suck in air. This is more difficult because water is heavy, so gravity pushes it down a lot. The more water, the more pressure. The more pressure, the easier to overcome the vacuum.

Viscosity is a factor here as well, that I won’t go into too much. Basically, the thicker something is, the harder it is to get through a small opening.

Water isn’t very thick, but it’s much thicker than air. So there’s a point where the opening is small enough that water has trouble getting through it without some pressure behind it. The force of gravity isn’t strong enough to push the water through the small opening, and the internal vacuum is too weak to suck air in since no water has left yet to create a vacuum. So there’s a standstill.

When this happens, you may notice that you can actually make the water flow outwards by agitating the bottle. Take a needle or toothpick, and swish it around the opening. You’ll notice that some water leaves the bottle. This causes a small vacuum to replace the water. Which sucks in air. The air displacing the water to rise upwards can destabilize gravitational pressure towards the opening, causing more water to leave, and more air to come in, and next thing you know, the whole thing is emptying due to a cycle of pressure. Water out. Vacuum created. Air in. Vacuum satisfied. Water out. Vacuum created…and so on.

Now, the point at which you reach that standstill depends on a LOT of factors. But it’s pretty much always a lot easier to accomplish with less water, because you have less downward pressure to fight against due to gravity.

Ok, that’s all well and good. But it still doesn’t explain why my “self-filling/gravity fed pet water bowl” “destabilized”, as nestcto referred to it. For that, keep scrolling through the thread (admittedly, I particularly resonated, for different reasons, with the last two):

- MrBulletPoints: Yeah if you were to jam something sharp into the top of that setup and make a hole, it would allow air in and the bowl would definitely overflow

- verronbc: Yeah… I like to call myself smart sometimes. The first bowl like this we had our dumb 70 lb dog was scared of the bubbles it made after he drank a bit out of the bowl. My simple solution, “Oh, I know I’ll just drill a hole in the top then the air will fill from the top” yeah in a moment of weakness I forgot exactly why and how these work and caused a lot of water to drain on the floor. My girlfriend still teases me about it.

- [deleted]: That’s why you have to punch a hole in the beer can before you shotgun it. It’s the same concept.

- stoic_amoeba: As an engineer, I’ve genuinely had this idea cross my mind because the bowl is HEAVY when you fill it all the way. Also, as engineer, I’m a bit ashamed I didn’t immediately realize how bad an idea that’d be. I haven’t done it, thank goodness, but I should know better.

Ahem. At least some of you likely realize what happened next. I went back and looked at that reservoir again, eventually realizing that after six years, the dent had finally become slightly compromised. If I filled the reservoir, turned upside-down from its normal position (so it was resting on its top), left it in the sink and waited a long time, I’d eventually find that a few drops of water had leaked out of it.

The same compromise was true (in reverse) for air, of course, when it was oriented correctly and in place. And it very well might have been like this for a while, counterbalanced by the frequent water intake of multiple pets. Drop the count down to one dog, though, and…puddles. We replaced it with a smaller dispenser from the same manufacturer, the first example of which also arrived from Amazon dented, believe it or not (I shipped it back for replacement this time):

and we’re happily back to an always-dry floor again.

I’ll close with a few photos of the original base, both initially intact and then disassembled:

The way these things work is that, after filling the reservoir with water, you screw on the lid:

then turn it upside down and quickly rotate it to lock it in place here:

The lid’s hole diameter is also key, by the way, as I learned one time when I put the reservoir in place without remembering to screw on the lid first (speaking of water all over the floor)…

Note the gap around the repository where the lid fits. I’m guessing this is where the air comes from to replace the displaced water in the reservoir, but I haven’t come across another Reddit thread to supplement my ignorance on this nuance. Reader insights on this, or anything else which my case study has stimulated, are as-always welcome in the comments!

—Brian Dipert is the Principal at Sierra Media and a former technical editor at EDN Magazine, where he still regularly contributes as a freelancer.

Related Content

The post A long-ago blow leads to water overflow: Who could know? appeared first on EDN.